Ernest Cole and the Malombo Jazz Men

Khanya Mashabela

Taking the cue of Matthew Blackman’s residency at A4, this path looks closely at a single image by Cole and then follows its connections to photojournalists, musicians, and artists from the mid-century onwards. – April 24, 2025

As Lewis Nkosi observed in the 1960s, a nexus of creative urban social life in South Africa was at its climax, resulting in the production of some of the most pivotal works of South African art, writing, photography and music. At the centre of this creative moment was South African jazz and its growing, culturally specific forms.Many of the photographers who worked for the magazines Zonk! and Drum were swept up in the fecundity of this ‘fabulous decade’, as Nkosi termed it. They captured this fugitive creative movement that the apartheid regime attempted to destroy.– Matthew Blackman

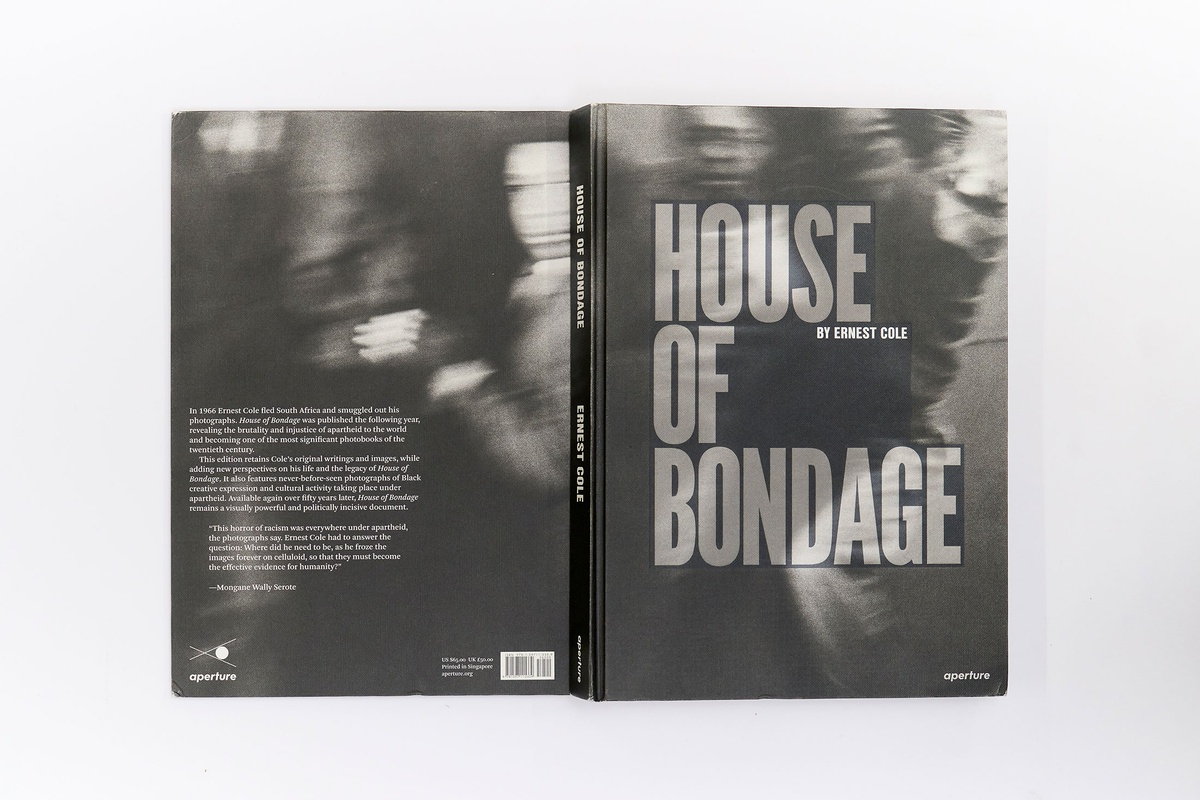

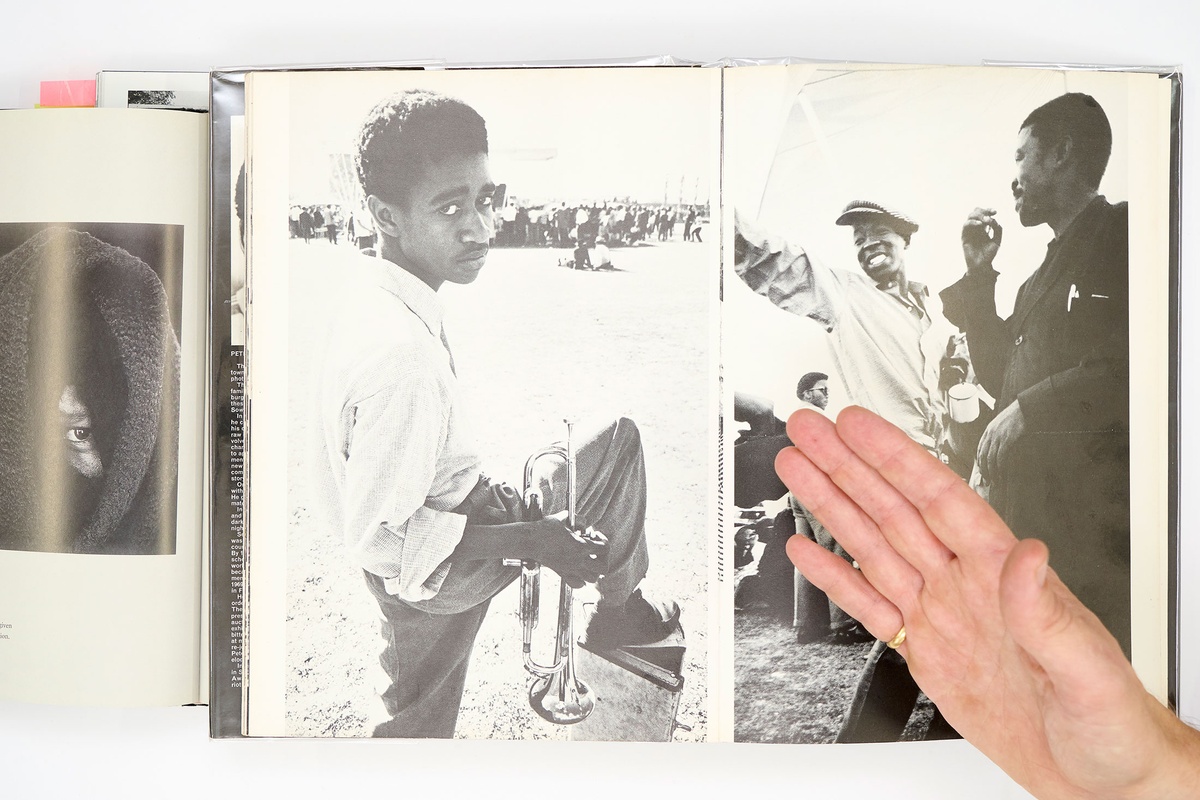

Most of the images in Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage (1967) reveal the daily cruelties of the apartheid state towards the black population. In contrast, the final chapter titled ‘Black Ingenuity’ (first published in the book’s 2022 edition) explores the vibrancy and inventiveness of cultural practice from South Africa’s townships.

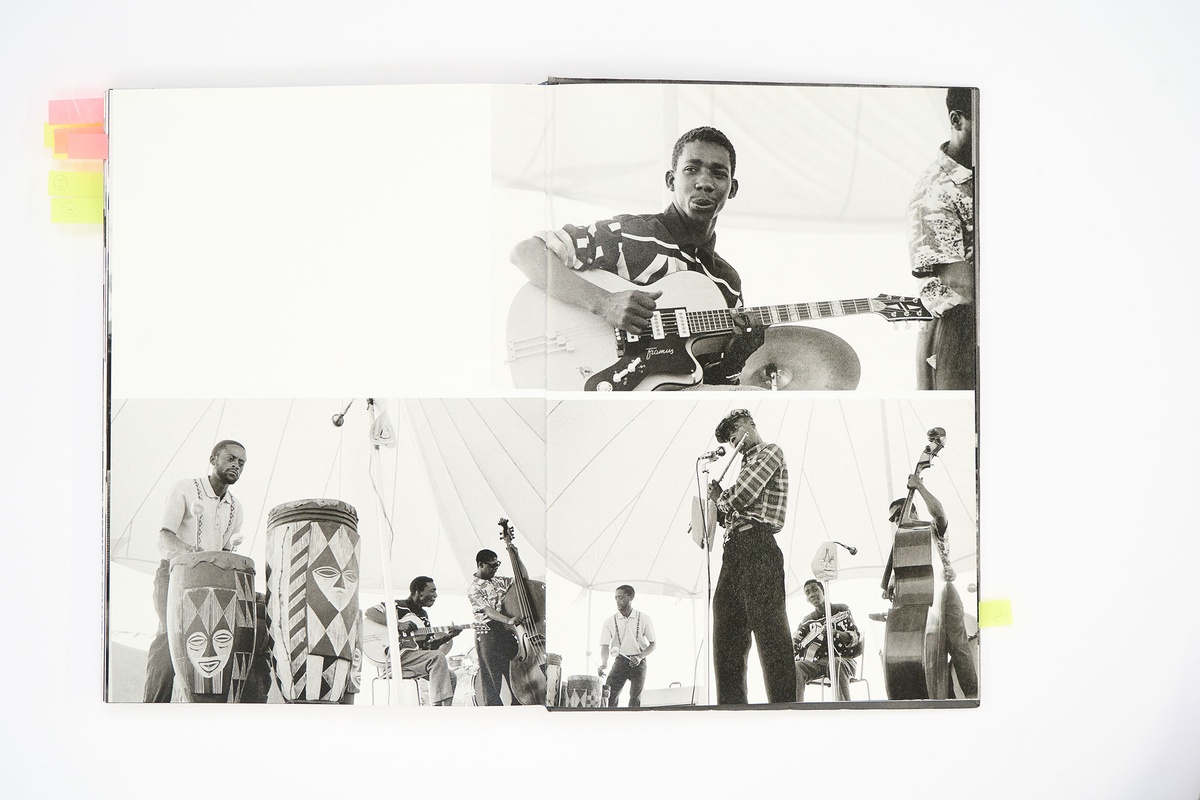

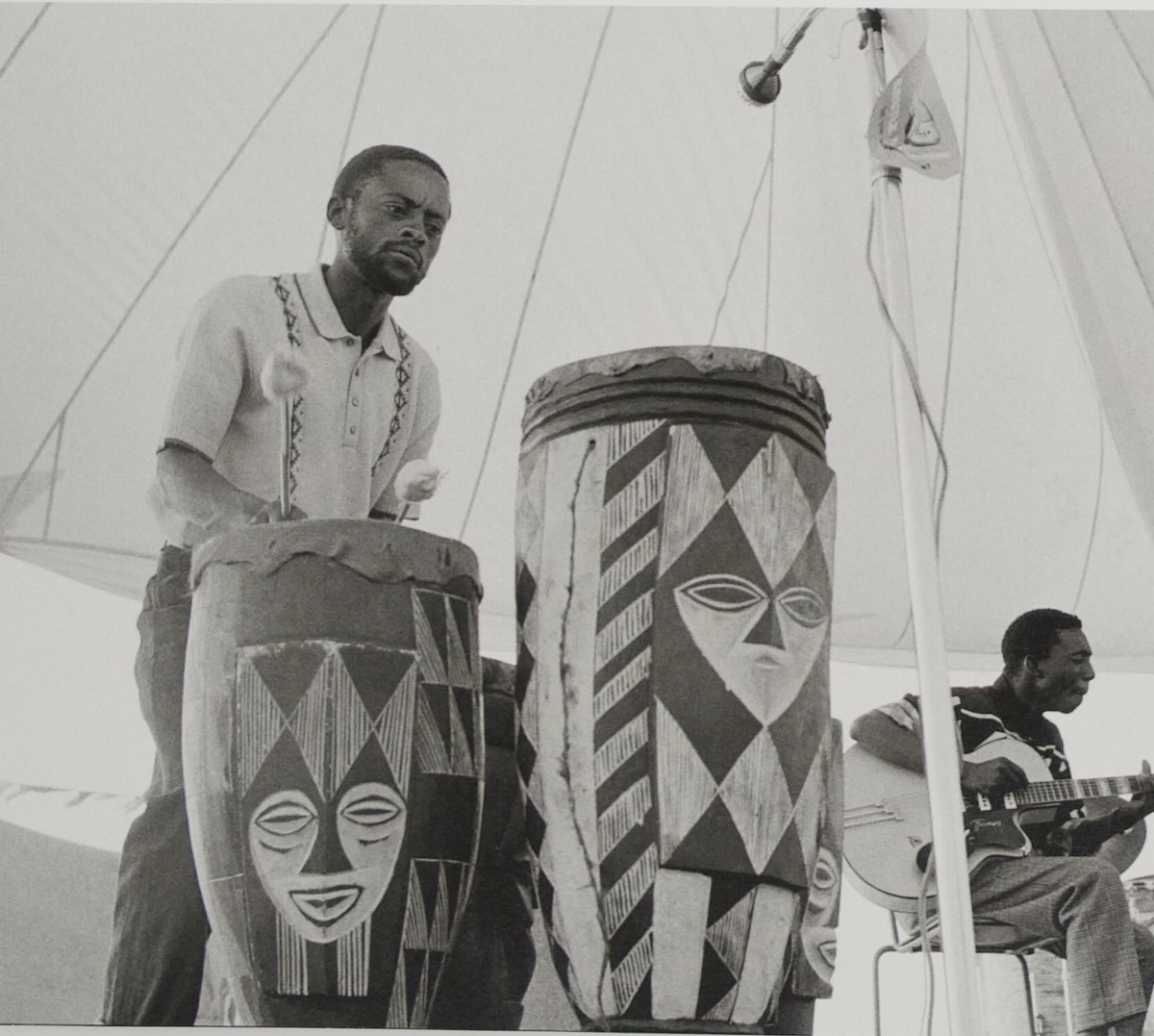

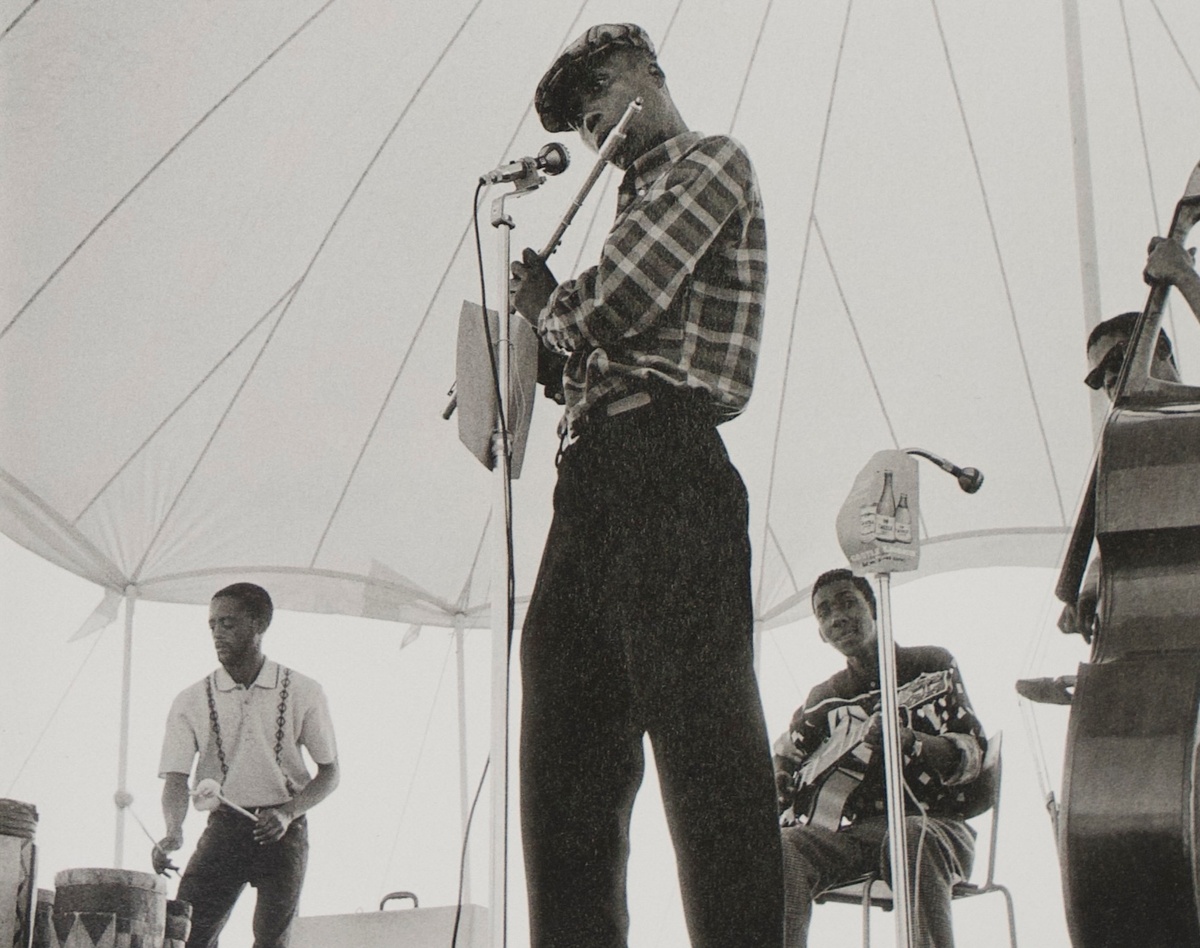

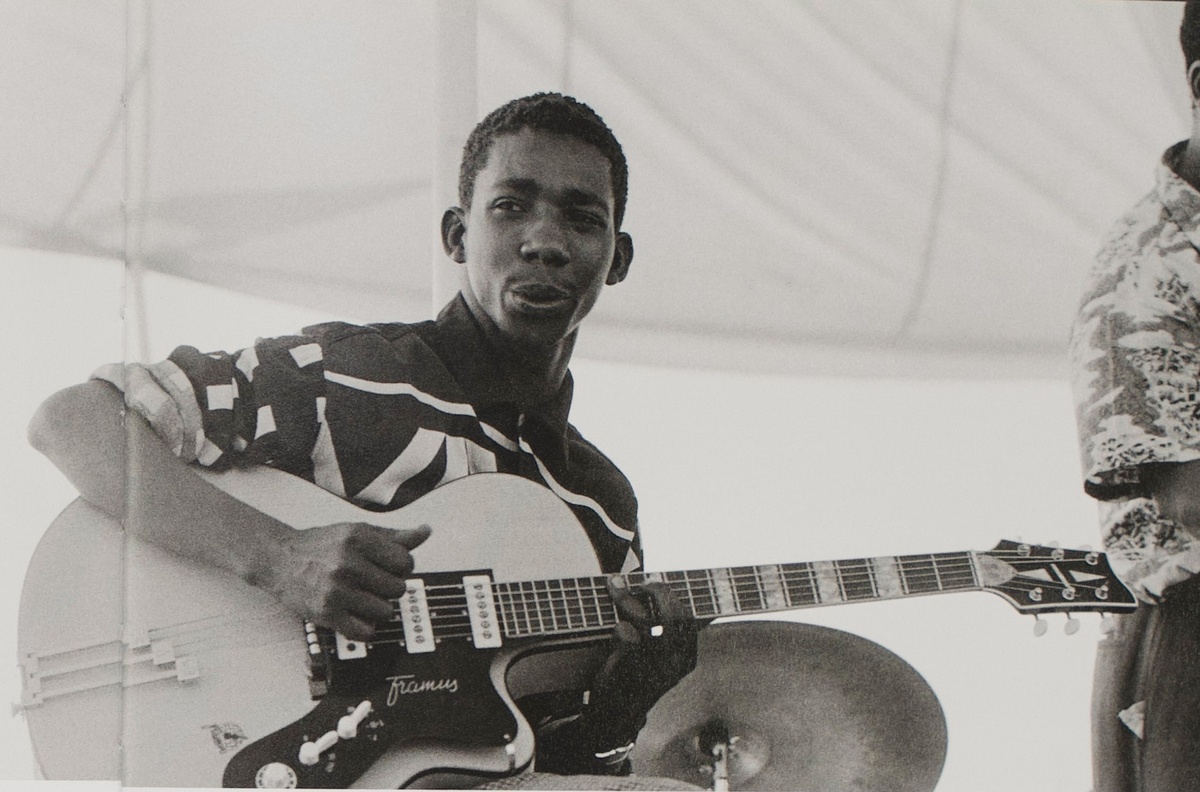

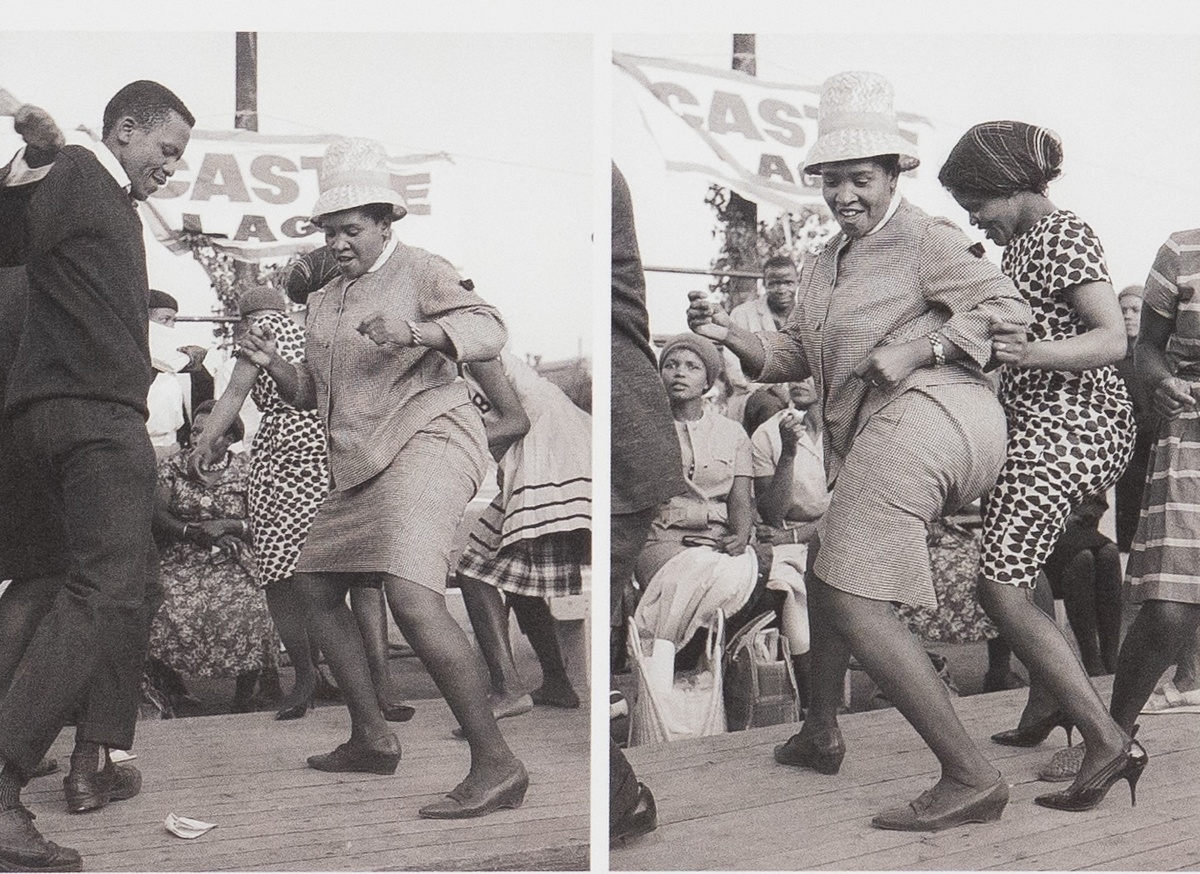

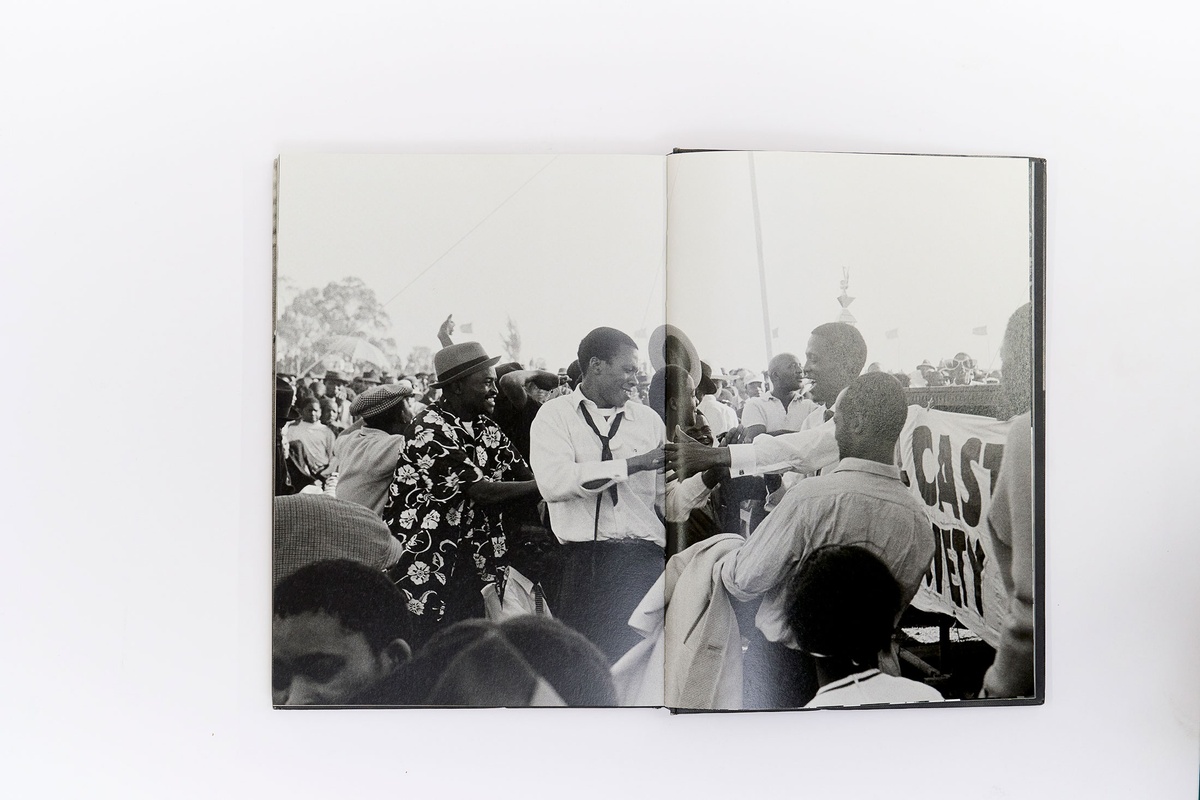

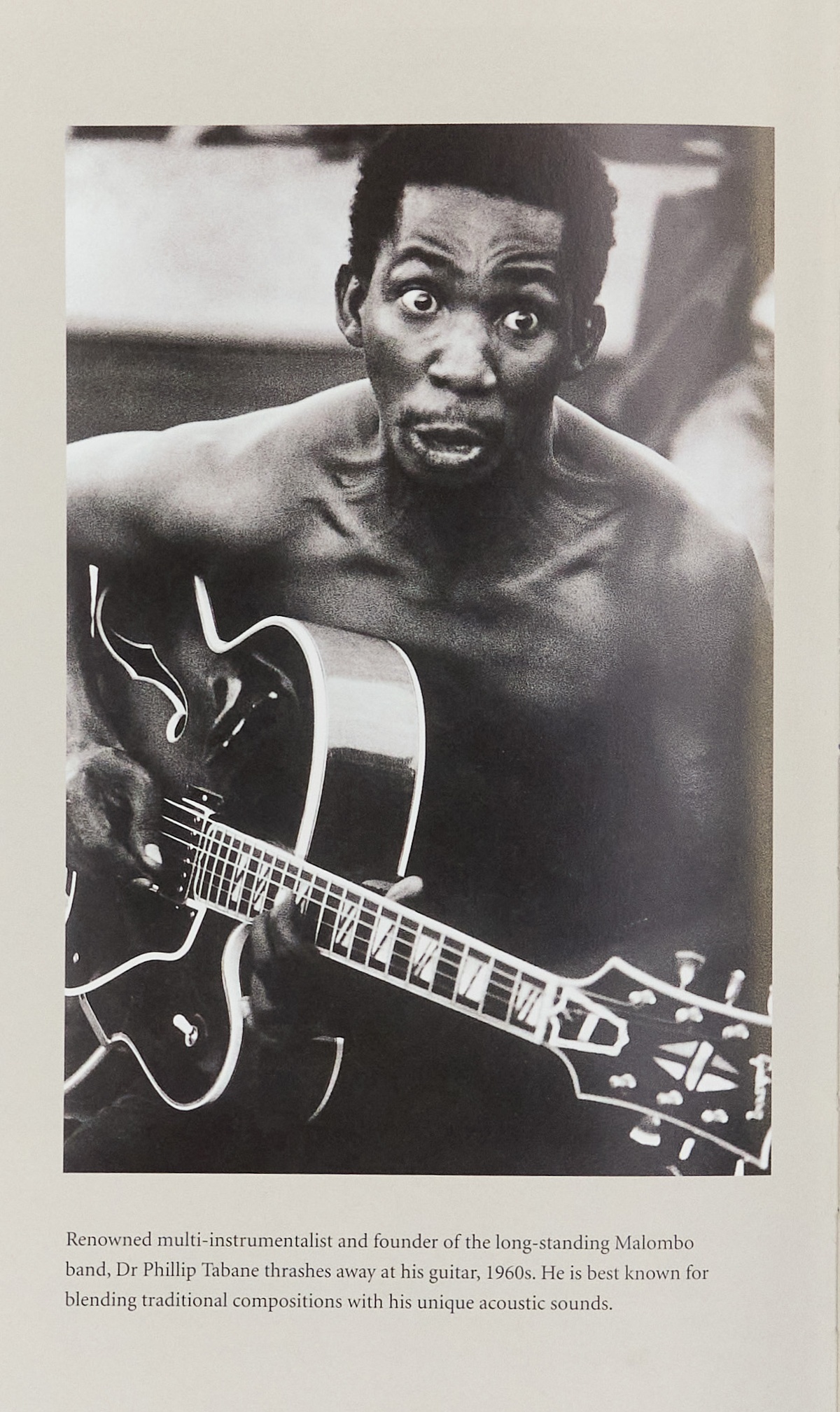

Pictured in ‘Black Ingenuity’ are the Malombo Jazz Men (later named the Malombo Jazz Makers) at the 1964 Castle Lager Jazz Festival in Orlando Stadium in Soweto, organised by Union Artists. The band was made up of Philip Tabane, Abbey Cindi, and Julian Bahula. Bahula and Cole were childhood friends.

In the early sixties, after we’d moved from Eersterust to Mamelodi, I got involved with two musicians, Philip Tabane and Abbey Cindi, and I became a musician. The three of us became the Malombo Jazz Men, Philip on guitar, Abbey on flute and myself, Julian, on drums. We became South Africa’s top jazz group. Ernest was always with us and he became a close friend of all three of us, and he took lots of photographs of us during our rehearsals.– Julian Bahula in an interview with researcher Gunilla Knape.

Alf Kumalo and Peter Magubane were also at Orlando Stadium that day, shooting images of the festival’s musicians and revellers.

I sold liquor, only for those who were interested in jazz; jazz lovers only. The rest, I didn’t serve them. At that time Julian was playing jazz with the Malombo Jazz Men, so after they had finished playing they usually came to me for refreshments. Even the reporters, like Alf Kumalo, usually came here.– Louie Bapelo on Mamelodi, a township outside of Pretoria, in the mid-1960s.

After a falling out with Tabane, Bahula and Cindi formed the Malombo Jazz Makers with Lucky Ranku.In 1974, Bahula and Ranku created the band Jabula while in exile in London. Bahula also organised a weekly jazz night at the 100 Club which became a meeting place for other exiled musicians and activists, and the legendary Festival of Africa Sounds (1983) at Alexandra Palace in honour of Nelson Mandela’s 65th birthday, adding momentum to the UK’s Anti-Apartheid Movement.

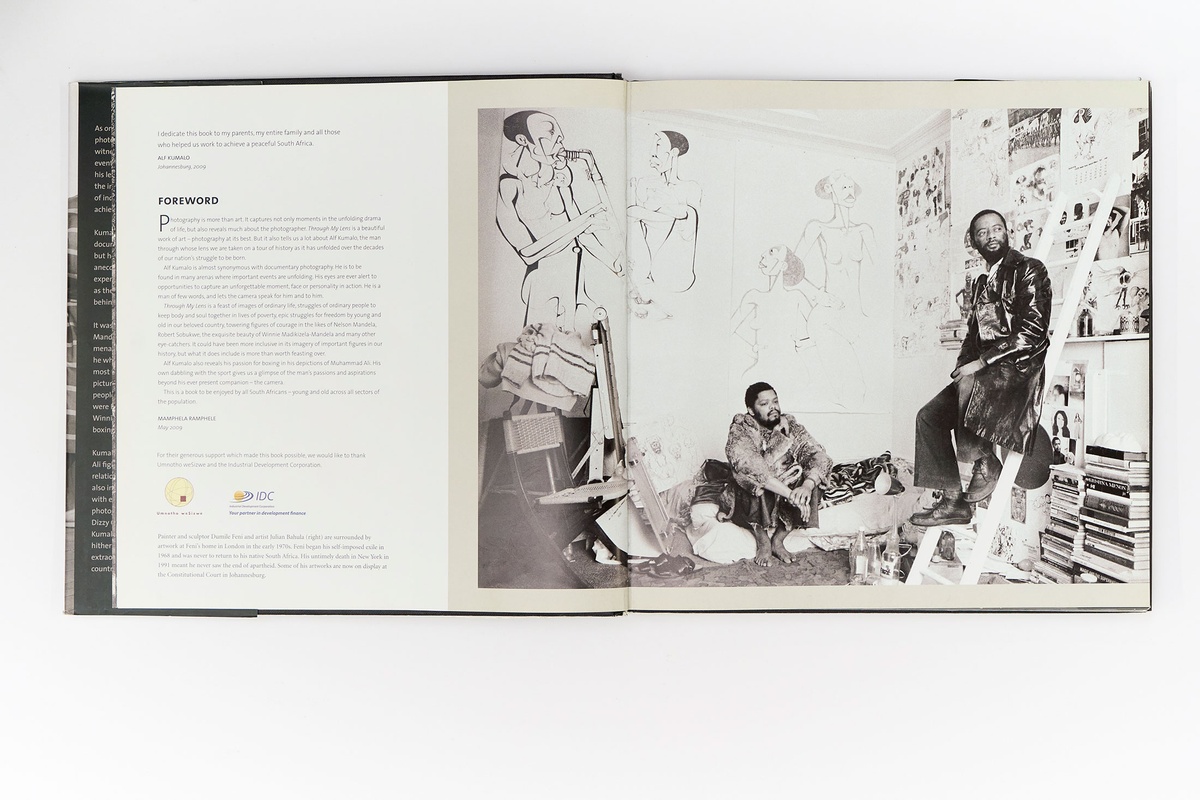

Artists were part of this dynamic scene of political exiles in London. Ranku lived with artist Dumile Feni in Streatham, and Kumalo photographed Feni and Bahula in Feni’s studio.

Tabane continued to play an influential role in South Africa’s jazz scene, and had a long and successful career. In the 1970s he toured the US, playing with preeminent musicians including Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock.

Jazz musicians contributed greatly to mid-century South Africa’s cultural and political landscape, and the Malombo Jazz Men are just one example. Beginning with Cole, Blackman utilised the available archive of documentary photography and writing to navigate the dynamics of a thriving milieu of significant figures including Gideon Nxumalo, Emily Motsieloa, John Koenakeefe Mohl, Gladys Mgudlandlu, Ephraim Ngatane, Bessie Head, and many more.In conversation with Daniel Malan and me, Blackman further elaborated on this ‘game’ of historical associations, which you can read about here.