Text:

Bongani Kona

Editor:

Sara de Beer

Design:

Ben Johnson

I cannot think of the dictatorship in my homeland without hearing the marching band. The marching band accompanied El Presidente wherever he went inside our little republic. Arriving at mass on Sundays, say, or at the house of a concubine at midnight. Those brass instruments drowned out the toll of the church bell, the urchins playing hopscotch or some such in the street, & the distant cry of birds. Even in our dreams, which were always dreams of plenty, ice creams & meat pies, a tuba or trombone groaned in E major. (Those were the days of hunger. We ate the hair of the rich, El Presidente’s friends and kinfolk. Hair that fell inside barbershops in the city centre). Of course, there were other sounds, too. The hiss of a tear gas canister. A thwack-thwack of a truncheon landing against the spine of a factory worker. Boots marching up & down on the tarmac. But it was the band that inspired our rebellion against El Presidente. We were driven mad by that sound. All of us. The birds grew restless & irritable. Parrots got into fights. Swans & gulls drank until they couldn’t fly or perch on a tree branch. Our little republic was in a state of disorder. One night a parliament of owls came to all of us, the children, in our dreams & told us to kill El Presidente. ‘You must kill El Presidente,’ the owls said. The next morning, at sunrise, all the children of the republic hid in the trenches by the roadside. We were armed with whatever we could find: a pair of shears, a cracked vase, an old arch lever file, stones & steel toe boots. We crouched by the roadside, as the sun rose over our heads, waiting for that dreadful sound to begin.

Madeleine began by projecting a trio of images on the screen: a coelacanth in the deep waters near the Comoros Islands, a male northern white rhino at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya, & a Yellow-breasted Bunting perched on a telephone wire.

Madeleine was the day’s last speaker & only a fraction of the symposium attendees had remained in their seats after Robert K.’s keynote address, ‘Art & the Apocalypse.’ Even the director of the Sanlam-Mutual Arts Institute, Dr. Marius Schoeman, looked deflated at having to stay behind to listen to Madeleine. A minor (failed?) visual artist suggested to him by an intern he found mildly attractive.

Madeleine adjusted the gooseneck microphone, leveling it to her height. ‘Unlike the destruction of the bomb,’ Madeleine said, ‘the disaster ruins everything, all the while leaving everything intact.1’

She had lived through dictatorships & a slew of military coups, Madeleine said. Coups which were announced the old fashioned way. Over the radio. The crackle of static before a male voice (and always it would be a male voice) announced that the country was being taken over by general so & so. ‘Because of where & how I grew up,’ Madeleine said, ‘I have always been listening out for the end of the world.’

‘Ethical failures are always entwined with imaginative failures,’ Madeleine said. ‘The Disaster Archive points to our collective incapacity to listen. We keep listening out for some loud bang that will herald the apocalypse,’ she said. ‘But the end is already here & it’s ongoing. The problem is we’re deaf to it.’

Madeleine was about to show a second set of images when she made eye contact with Dr. Marius Schoeman. The director frantically tapped his wrist. ‘Fifteen minutes,’ Madeleine heard him whisper. ‘Your fifteen minutes is up.’

I will remember it for the rest of my life. The day our voices rescued life from death. It was the afternoon Pa took me to Gallows Hill to bid farewell to the arm wrestling champion of the 153rd State. At the hour of his execution, The Colonel stood proud before us, dressed in his signature attire – a battle helmet, gold tights and black combat boots with no laces. When the priest asked if he had any last words, The Colonel looked up, eyes squinting into the midday sun, & cleared his throat. A hush fell over us. Then, the Colonel began to sing:

The world's smallest guitar is playing my favourite song.2

At the sound of his voice, we tipped our heads to the sky, & began singing in unison.

The world's smallest guitar is playing my favourite song.

Afterwards, the priest asked if we may bow our heads to pray. I stared ahead, at the hangman's tortoise-coloured sandals, as all around me heads were lowered down to the earth. The priest made the sign of the cross & asked the Lord for mercy as the hangman fixed the rope around The Colonel's neck. ‘Can you imagine doing this shit job my brother?' I heard the hangman say, taking a drag from the cigarette dangling from his lips. 'I actually wanted to be a salesman.'

Moments before he slipped through the hangman's trap door, The Colonel performed one final act. He raised his right arm to the crowd, a salute, & began a slow marching drill on the spot. The way The Colonel moved his feet…What beauty!...like a waltz: one-two-three/one-two-three. It was then when we resolved that we would not let him die. We resumed singing again & when the trap door fell open The Colonel floated up to the sky on the power of our voices. We would keep him alive that way. Even if it meant singing the same song for days, months, years. Our voices would continue to ring out. Not another person would die because we chose to fall silent.

Bongani Kona is a writer and editor based in Cape Town, South Africa.

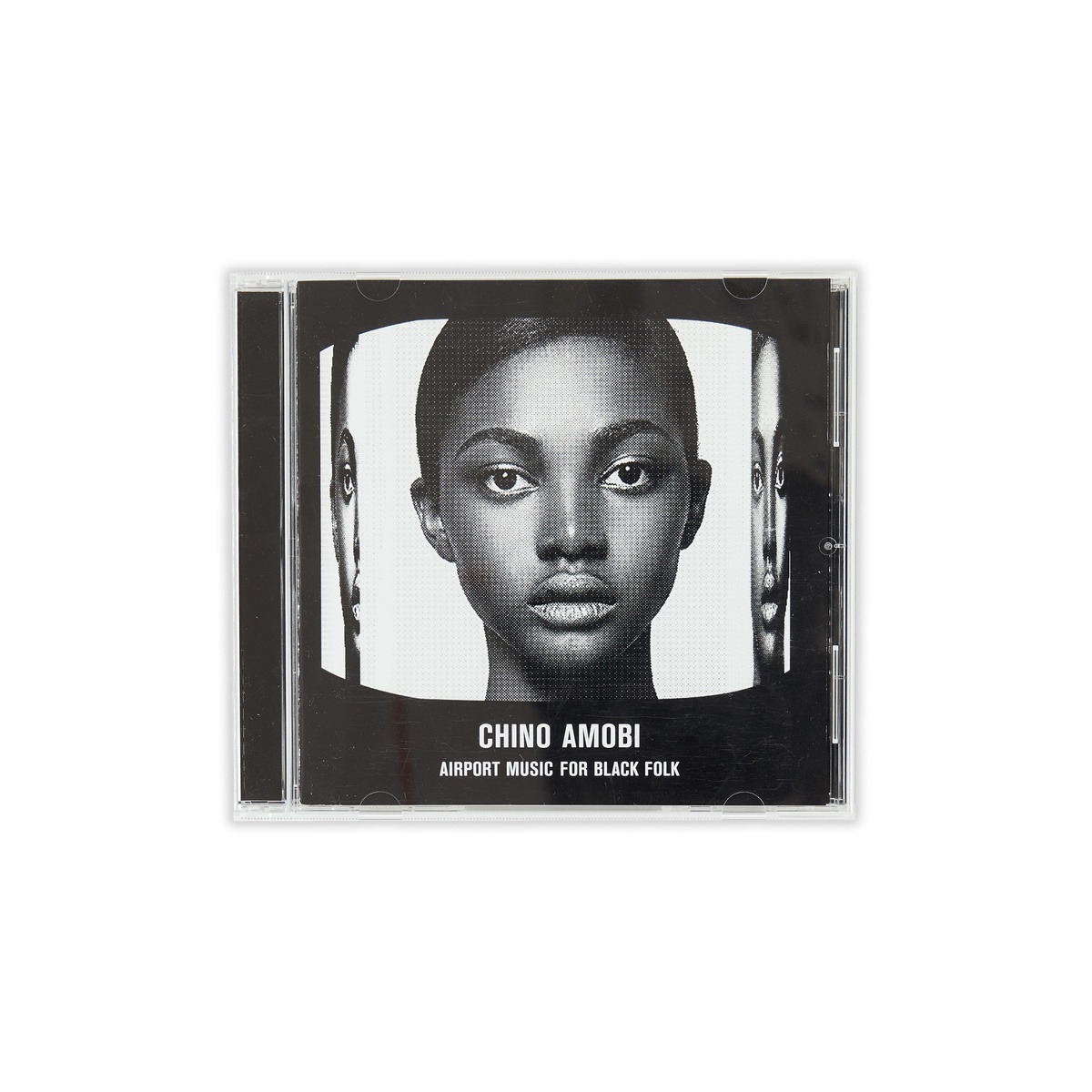

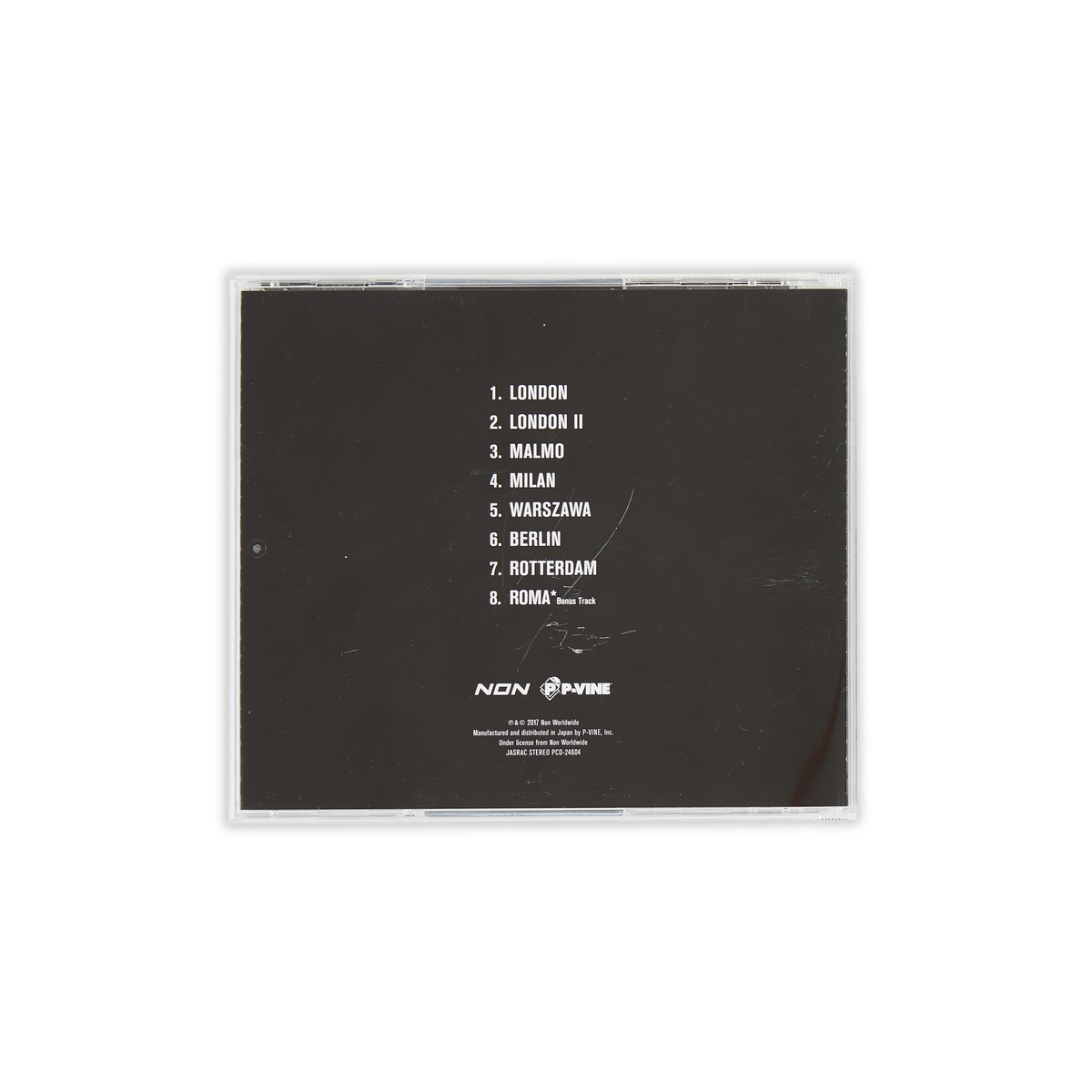

This essay was commissioned for the exhibition Sounding the Void, Imaging the Orchestra V.1 curated by Bhavisha Panchia at A4 Arts Foundation, 23 May- 22 August 2019. Featuring works by artists Vivian Caccuri, Chris Chafe, Nick Cave, Andrew Pekler, Robin Rhode, Sahel Sounds, and Jenna Sutela, in addition to a selection of podcasts from Phantom Power and audio media from Nothing to Commit Records, the selected artworks utilised audio phenomena that vary in medium; from vinyl records, video and installation to podcasts, web releases and performance lectures. A public program of talks, workshops and seminars accompanied the exhibition.