J.G. I'd like to make a few opening notes and to offer some context to this remarkable project, which is something very close to the heart, organisationally and personally, for many of us in this room. The intention today was primarily to gather two teams – Igshaan's studio, an amazing community of makers, and the A4 team – to celebrate this process that has spanned almost five years in different ways and forms. This moment is not only an opportunity to celebrate together, but also to think together and maybe close a loop – or open another one.

In 2020, Igshaan and his team relocated to A4's gallery and turned it into their studio for five months. Partly because of this project, we've since come to understand A4 as something of a studio itself, where Igshaan's Open Production was the first elaborate prototype: having an artist's studio and team in-house with us, we became an extension of what was happening. We were given access into how Igshaan’s process unfolded. It was an opportunity for our organisation to build our capacities in relation to the practitioner’s studio practice, to ask, what is needed here? And to work together to do our best to provide that, growing ideas together. It was also a moment in terms of the transformation of Igshaan’s practice itself, because some interesting things happened around that time – things that are captured in this book. Igshaan’s tracking and tracing of lives lived in homes was extending out into the world as he began following paths walked in the public domain, asking how those could be translated into something intimate, too. These pages address those forces.

Then there is a second coordinate that we did not anticipate. Because the book is so intricately detailed and ambitious, it took a long time to make, and in that time, the covers – which are astonishing insights into a whole series of projects – have come to be something in and of themselves. They are an archive of projects done, of works made that now exist in various parts of the world. A few are propositions for works to come. So, in addition to the book holding a particular story at a particular time in its contents, these bound objects reflect something of the past and project into the future.

As the books came alive and as they entered this room, as we saw this constellation, it felt more and more important to gather and hold them all together for a moment before they go off in different directions – to see them as a family as we mark this time.

I.A. As we begin, I want to point to that folder on the About Wall. That’s where all of this started. Josh and Ben began noticing the debris while we were using A4’s space as a studio, picking up these details. It’s these details that became the starting point of the conversation around the book.

The truth is that this is often how new works develop. Something drops, quite by accident – you pick up something that’s fallen, and a project begins. You notice something – a fragment – and you grab hold of it and pursue it. You end up at an unexpected destination

The book project similarly started with these details: studio debris, those things that typically get thrown away.

Something that has always been important to me in my practice is to hold more than one perspective or view in mind. The details, the close-ups – this kind of zooming in and inspecting things at the most micro level possible – but at the same time holding them at a more distant view. This is like using Google Earth, as we began doing here, to look at these pathways and desire lines that cross certain boundaries – this idea is captured in the book. It focuses on details, but also makes space for a wider perspective.

J.G. Looking backwards briefly, I remember the early phases when you started weaving on the loom.

I.A. It came from my idea of unravelling prayer rugs and then reweaving them as a way of making my own form of Islam in the process of dealing with my spirituality. This was the intention. Ultimately, it became quite difficult. But that's where it started – with me weaving from one point to the other in a very simple plane, up and down. That was about ten years ago now. What's made visible in these covers is how the techniques have evolved over time, and how we've been able to introduce new materials – like the beads, initially, and then, in time, mohair, chains, some fabric pieces.

J.G. Could you pick a cover that gestures to a particular moment? One that says something particular about a particular innovation.

I.A. Here's one. Mohair is probably the material that was most recently introduced. This wool, the way it looks, echoes my interest in dust. I've spoken about dust or thought about dust in different ways before, specifically in relation to the rieldans, the dance that I grew up witnessing with my grandparents, and the dust clouds that are produced during this dance. I make these wire installations, as many of you know, trying to mimic how dust and dust particles behave in space. The mohair was a nice way to represent that dusty feeling in these woven surfaces.

Some, if not most, of these covers relate to much larger works. This is one of the newest works. It will only be shown next year at the Guggenheim in Bilbao. It's made up of four large panels stitched together. It's a giant piece. This was a test of a kind that we did before we started on the larger work. We later turned it into a cover.

Some of the covers were tests for larger works; others were made retrospectively, referencing past pieces. There was no rule I followed with these covers. I thought I might use this opportunity to play around with things that I'm thinking about, with new works I might want to make, but also to return to old works that I haven't seen in a long time, or feel disconnected from, to see if there are techniques I might want to reintroduce.

Here’s an example. Years ago, I played around with unwoven sections, or embellished holes. These ended up in my archive of failures. They never really turned into anything, not until much later. During my residency at Zeitz MOCAA, I unpacked these unsuccessful experiments and put them on the wall. And I was re-inspired by them. I thought, maybe now is the right time to pursue them. It turned into many large works, eventually.

J.G. In your earlier pieces, long before the Tapyt series – there were lots of gaps and holes, and the material was –

I.A. Less ‘refined’, I'd say. Five years ago, I decided to push the works into this much more refined space – in the weaving, in the way we completed the edges. If you look at earlier works, we didn't trim the excess ropes, you can still see them dangling down from the back. We don't do that anymore and, I will say that, at the moment, there is a desire to pull back somewhat to that rougher and unpolished feeling.

J.G. How do you do that? How do you reinvigorate a certain sensibility?

I.A. I don't think of it as going back – not unless I can time travel back to being 29 or 28. Life has happened. I'm no longer that person. I'm 40-odd years old now. So it won’t be about going back there. It would be a coming together of this refinement and those other, older processes – of letting things be both complete and incomplete.

J.G. Where do the shells come from? Where do they feature? Here's an example.

I.A. These shells are details of my own life growing up. I was raised by my aunts and my grandmother, and these were always in the home. Shells covered everything as decoration. Growing up in Cape Town, going to the beach – the shell is a detail that I latch onto as something that I feel could pull me back into an earlier life in terms of whatever inquiry I might have about myself. Cowrie shells have a history of being used as currency in Africa, and some will assume this is the reference, but to be honest, rather than those cultural or historical associations, the shell is a personal detail for me. The chain is the same. Often, the textures and the palettes of my works draw on memories of my grandmother and her own personal aesthetics. This is sometimes my inspiration.

J.G. Some covers are works made; some are works to come; some are tests for works that never came to be, where the ‘work’ exists now only in the cover.

I.A. Exactly. Most of them have larger works associated with them. The work for this purple one was in a show called Holy Terrain that some of you might have seen. But then here is another one that won't be made, another work that I tested but will not pursue.

Years of experience become your intuition. And so as you work, you come to operate from there, from that knowledge. You just know that this thing is not everything it can be. And so you keep on pushing until it feels full or complete. And you know when it's complete. The truth is that if a work were to come back into the studio, give it a year, none of it will stay the same. It will continue to be made. Whatever comes back, I tell the gallery, if a work comes back into the studio, it won't survive. It's going to turn into something else. If you want to hold on to the artwork and keep it, don't return it to the studio. I think these things, these artworks, these books, I could probably continue to work on them.

At an upcoming exhibition next year, I’ll lay out all of these failures that I’ve been hiding, works that I once thought of as unsuccessful. The archive of my failures. For example, here, in book form, this one worked, and so we pursued making it into a large work. We worked on it for a week and got quite far. But ultimately, we took it off the loom and started the whole process anew. This book is how the same work was ultimately materialised.

J.G. So this work never happened? That’s beautiful in its own right.

I.A. There’s another one that similarly never happened.

But, of course, a work is never really unsuccessful; it’s just out of time. You just have to find the right time for the idea to fully be carried through to its end. You have to have the energy for it.

It’s going to be a good process for me to reflect on the past ten years of weaving. We started with this very basic weaving from left to right, where we now weave up to seven different materials at once, mixing them together, creating new textures and tones that are not necessarily represented in the materials we work with. Whereas before, whatever colour I bought, that would be the colour that I would be dealing with. But it took a while.

J.G. What I particularly love about the book covers is their scale. Typically, with your bigger pieces, you have the advantage – to your point earlier – of the holistic view. You can interpret them from a distance, and as you come closer, they get more elaborate, and they keep giving. But these have a wonderful intimacy that is retained.

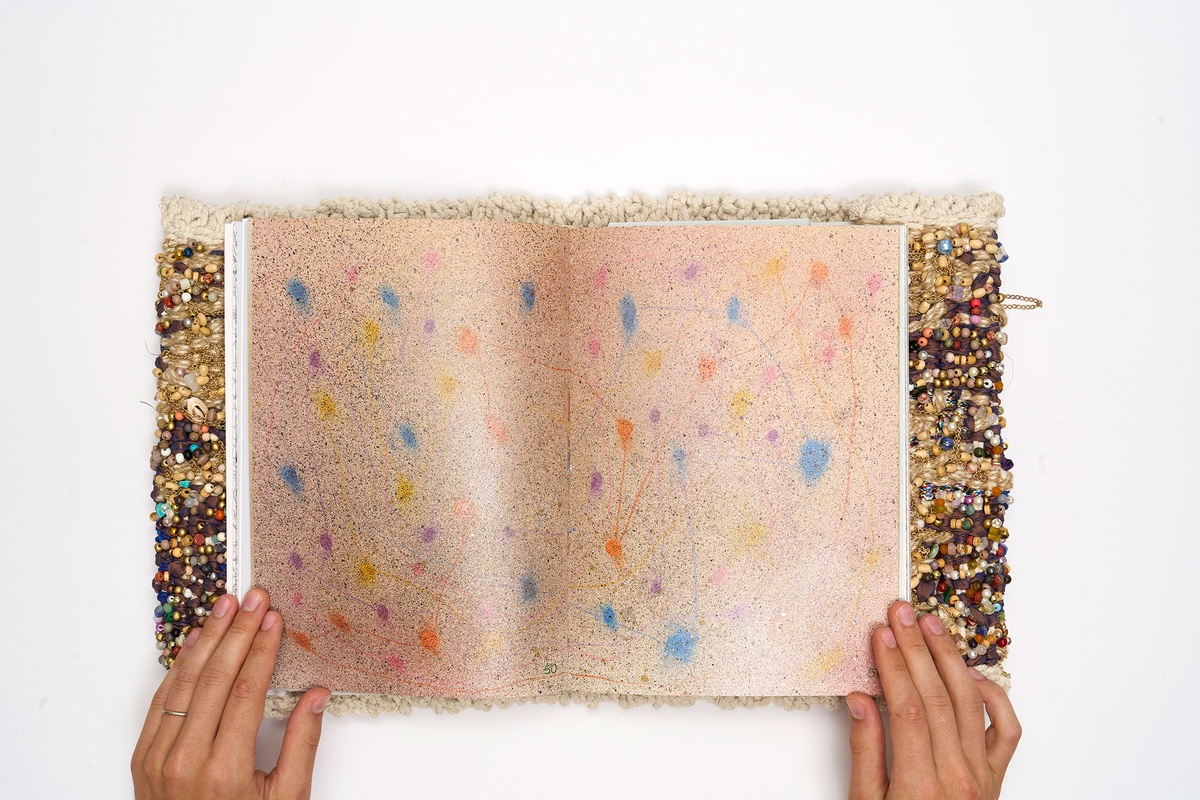

I.A. This is reflected in their contents too, with the transparencies and die-cuts, all those details of details. We had decided from the beginning that the book would include some blank pages for me to interact with my nieces, my family's kids, who are part of the studio. They range in age from two years old to 17. They are always present – so I wanted them to feature in the books. They all drew something. I asked them to stay away from representational drawings, to rather make their own marks and lines. We had a full day together, painting and drawing.

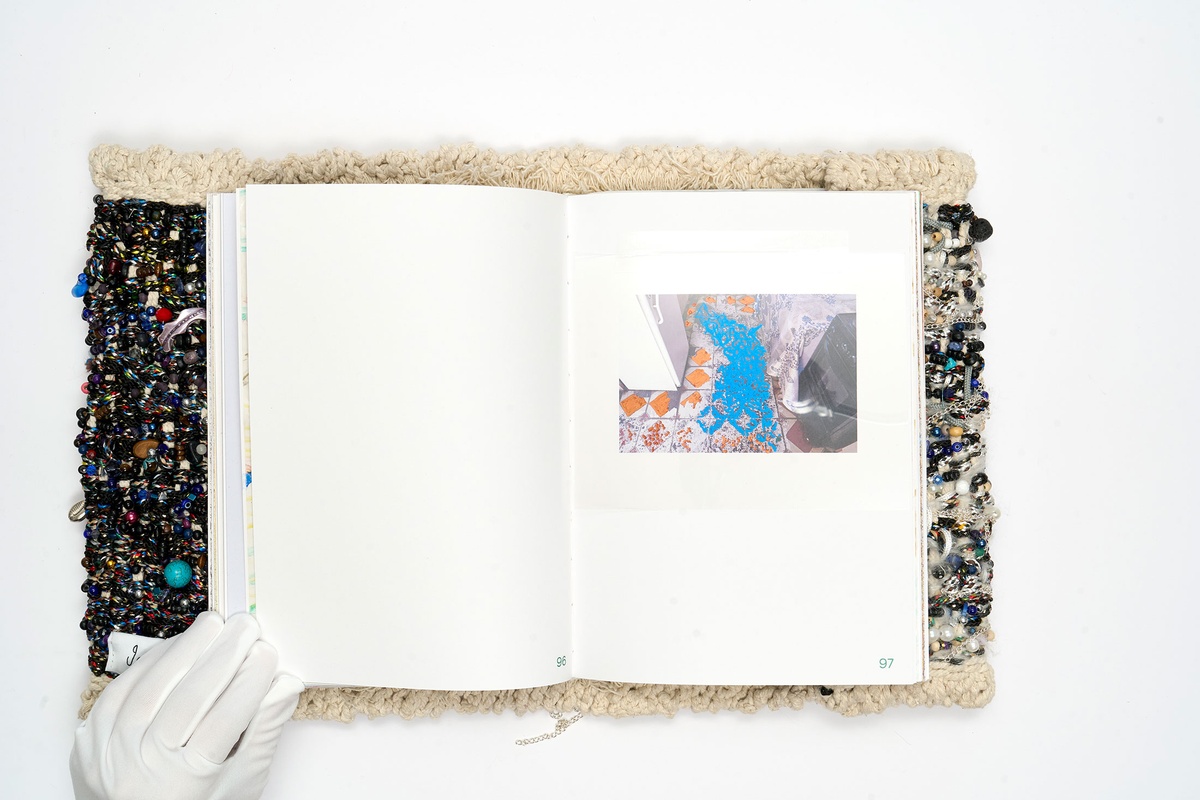

On other pages, we wanted to outline the desire line process that we were doing at A4, which began while we were here. In that instance, we used a photograph and started drawing on top of the image with these paint pens, marking out exactly which part of the map I was going to represent in the tapestries. These drawings were eventually blown up and woven. And so, in the book, we did something similar, using these transparent plastic sheets and showing what the process would have been. At that time, with Tapyt, we would go into people's homes in Bonteheuwel belonging to the families we worked with, whose pathways we traced out. The work upstairs in A4’s Gallery in the current exhibition Sightlines, 11B Larch weg (ii) (2019–2020), is a good example of someone's home from the front door to the back door, and the path that formed in that space over time. In the book, I did something similar. We took a picture of someone's home – the floor in someone's home – and sketched over the image with felt-tip pens.

The sheets of plastic on the walls in this installation are the actual material used in the studio. We have included parts of sheets like this, cut from the plastic tracings, in the book. The marks are intentional. These patterns and tracings of the floors are my way of speaking to the weavers. These translate the energy produced by the marks and how the colours overlap.

In this one, for instance, the crazy marks represent a particular type of weaving where different materials are woven into each other. And you'll see there are moments where the green, the red and the silver coincide, and so the weavers will know exactly how to change the combination of materials. There are more open areas, too. In other drawings, which we don't have here, there is crosshatching over dots, which shows an overlap with something else.

With special thanks to –

J.G. Ben Johnson, who designed the book with such precision; Candice Ježek, an exceptional bookmaker without whom this would not have been possible; Sara de Beer, the editor and writer, who captured and distilled the ideas in this book to make one incisive line through it; Kyle Morland, who created this installation, who made this moment happen; and Janos Cserhati, who took hold of this project, weaving people together, working closely with the Igshaan's studio – it was a monumental task.

Then there’s your studio, Igshaan – Monique du Plessis, the team at large – who have continued to welcome us into the space. Working with you all has been a genuine pleasure.

I.A. I’d like to thank them, too. I have an incredible team. There's this kind of fuzziness between my working team and my family at large. I don't always know where it starts and stops. Everything blends together. And I do think it shows in the final product, this closeness that we share. So – thank you.