L.B. Perhaps we could begin by reprising the story of the two archives – the dendrological records you inherited and your accumulated tree photographs. How did they come about, and how do they intersect? Did they exist independently, or was the second a response to the first?

M.T. Well, they come from the same camera; that is, first and foremost, their link. The camera, in turn, comes from my godfather, who is a member of the South African Dendrological Society. He joined in the early 80s and soon after befriended the founders, a married couple who, by and large, actually were the society. They were not only organising trips but also photographing trees, recording trees, measuring and advocating for trees – doing all sorts of things with trees. As I understand it, in the mid-90s, the husband, Dr Fried von Breitenbach, passed away in a car accident, and my godfather took it upon himself to financially support his wife in the absence of her spouse. And I think out of perhaps pride or shame, or something in between pride or shame, the woman found it difficult to accept money from my godfather, so he would buy things from her – up to and including a house – and the camera was among the things that he bought. When he bought the house, the house from which they once ran this entire dendrological operation, he inherited the archive. There’s probably a gap of about ten years between when my godfather, who had no interest in the camera or use for it, first purchased it and when I received it. I'd recently graduated with my design degree and I suppose he thought, well, maybe Michael will have a use for this thing. So that's how I came into the camera, which I used for a decade before visiting my godfather and coming across this archive of photographs.

L.B. As I recall, there are two cameras, yes?

M.T. Yeah, there are two cameras. There is the one I work with, a Hasselblad 500cm, which is quite a common square-format camera. The other is a Hasselblad SWC/M, a fixed-lens, super-wide camera I've never really known how to use. I think that that camera was designed specifically for industrial use, for photographing the insides of boilers and so on. But if you're photographing big, wide things, such as the sprawling types of trees you find on the Highveld, I can imagine them being useful. That said, in the negatives I've looked at, I have never found any photographs that point towards that camera.

L.B. So it wasn't necessarily used by its previous owner –

M.T. And now it isn't necessarily used by me. So that's the other one. And there's actually a Leica, a third camera, which my godfather also gave me, which they definitely did use. But the majority of pictures, almost all of them included in the archive, come out of that Hasselblad.

L.B. Did the knowledge that this camera had been used to photograph trees seed the thought to begin collecting your own images of trees? Or was this incidental? Some of the photographs from your own collection appear to belong to other projects – their inclusion here is happenstance; a tree intervenes in the frame. Was this collection of trees the result of a retrospective review of your photographs or a working logic as you accumulated them?

M.T. As I mentioned, there was this ten-year gap between my receiving the camera and actually spending time in the house that belonged to its original owners or photographers. But then ‘photographers’ doesn't feel like the right word because they were using the camera in a particular way –

L.B. In service of something else –

M.T. In a very materialist, scientifically exacting sense. So, no, I'd never really set out to photograph trees. There was no dialogue between what I was using the camera for and what it had been used for previously. I've had a longstanding interest in picture-making in all sorts of senses, and photography is my first medium.

L.B. I think this is important – you’re primarily a painter in my mind nowadays.

M.T. But photographs came first. And that comes from my father. When we were kids, he used to set up these slideshows at home and show us his pictures on Sunday nights. When my dad was around my age or a bit younger, he spent a lot of time photographing steam trains – I've counted over 3000 negatives. Nothing ever came of his project. It was not art-world related, much more of a hobbyist endeavour. He was a member of the Rand Model Engineers, really into trains in general. When I was probably around 15 or 16, my first photography project was also centred on trains, making pictures of graffiti on parked Metrorail trains at the Strand Yards. All this to say, there was already this interest in photographing a given subject in series. But my photos of trees didn’t come about like that.

I've been hawking these envelopes, this archival matter, around since I brought them home in 2017 after a visit to Pretoria. By then, I’d become acquainted with not only photographers like David Goldblatt but also people like Ed Ruscha, who I was very taken with, people who were using photography in more interesting ways beyond the documentary, who were interested in seriality but also in the pictures beyond their subject matter (I’m thinking specifically of Ruscha’s Los Angeles Apartments). So when I came into these dendrological photographs, I thought, well, there’s something here; I just wasn’t quite sure what it was. I would periodically drag them out and chew someone's ear off about them. And I think that's how Daniel, your colleague at A4, got wind of the collection.

Towards the end of last year, he called me and said, Mike, come over and bring those tree photographs – not your photographs, but these inherited or acquired pictures. I thought, amazing! Finally, I can indulge in some sort of archival practice or whatever. I very excitedly rang up my godfather, and said, I know what to do with all this stuff that is littering the house you've bought. And he said, that's all well and fine, but I've destroyed the rest of the archive.

My heart sank because I've only really got about 40 of these envelopes.

L.B. Out of how many?

M.T. Out of… I have no idea. I mean, that house was so full of stuff. Three garages of things – it was a proper Pretoria North spec house. You know – three bathrooms, four bedrooms, really made for a growing family. And it was just these two childless, elderly people and lots and lots and lots and lots of material. So I rang my godfather up, and I was like, finally, I have an opportunity to – this is in my head – do something, I suppose, in the footsteps of, or emulating, some people whose work I really admire, or maybe do something in dialogue with them, rather. And he was very matter-of-fact: I've destroyed the pictures. He mentioned that he tried to donate them to the University of Pretoria and that they weren’t interested in the archive; it would be too much of a burden for them to store and digitise them. Other members of the Dendrological Society, of which my godfather is still a member, suggested they just destroy them. They're of no use. They're over 30 years old. The trees are, if not dead, larger – and these photographs, which served a very scientific purpose at the time, no longer apply.

When he said, I've destroyed them, I thought, well, here's another strike against my ambitions. And in despair, back at the studio, I started rifling through my own photographs, specifically those I had made with this camera. I thought, let me see if I can supplement this now broken archive with my own pictures.

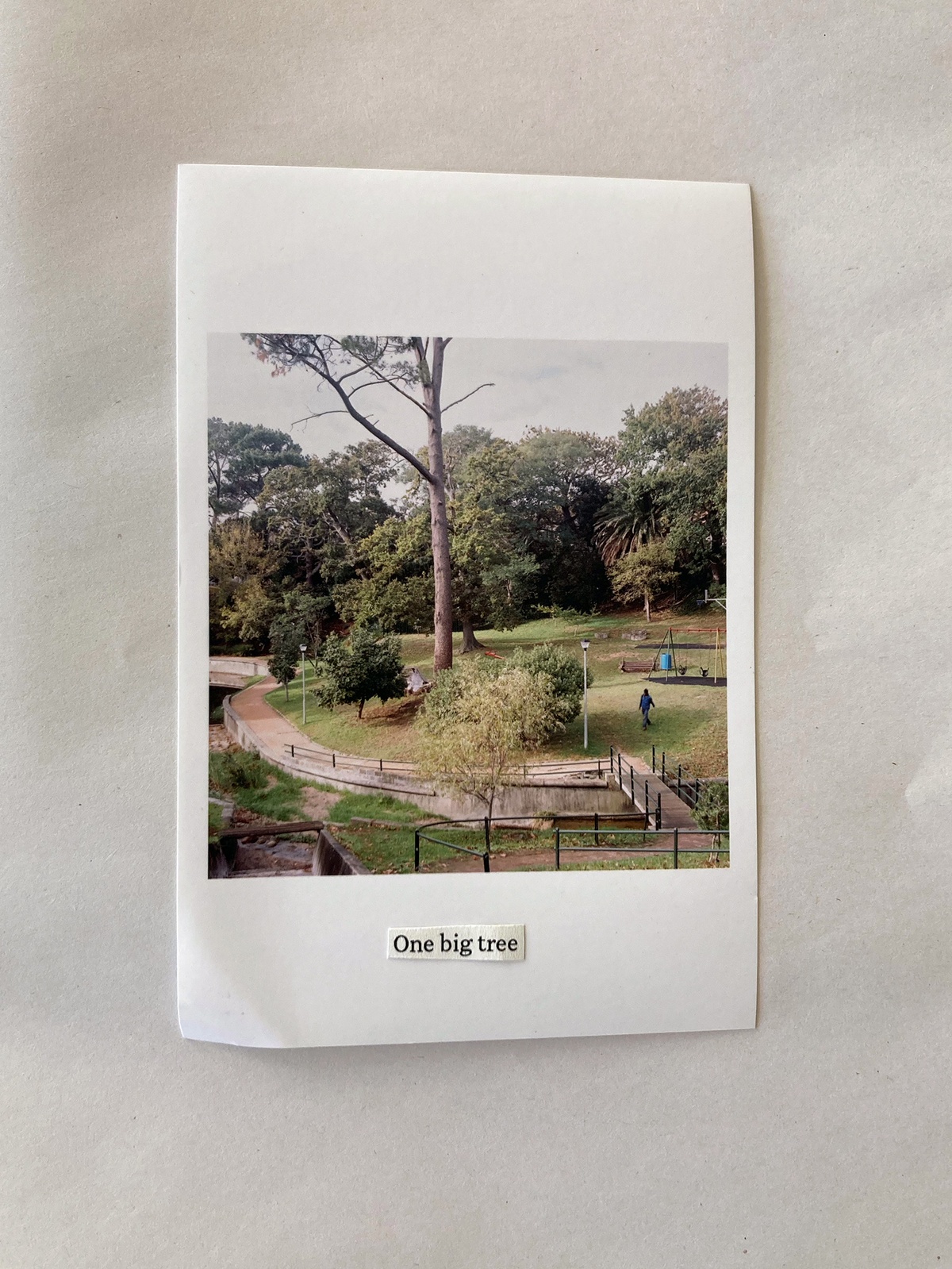

I only remembered ever photographing a single tree consciously, a tree on Bloem or Pepper Street that had been chopped down. That was the only one I remembered taking with the thought, I want to photograph this tree. Along the way, I found others in my serial photographs of trains and banks, and in my pictures of protesters. There's a whole body of work from Poland. Incidental trees in my ‘I would like to photograph this’ pictures. So, I thought, let me find others. When I was photographing a lot, I would always make prints so I didn’t have to dig through negatives or scans. And in looking for those prints, I started making a pile of all the pictures of mine made with this camera that had a tree as the unintended subject.

L.B. I think that's why the juxtaposition is so compelling because, obviously, with the dendrological photos, the tree is the stated subject. There's occasionally a man for scale who is functional, a purposeful inclusion. But in your pictures, the tree is often oblique – and it's the more obscure of these I find myself drawn to, the top of a tree seen over a Vibracrete wall or the tree on a protester’s T-shirt.

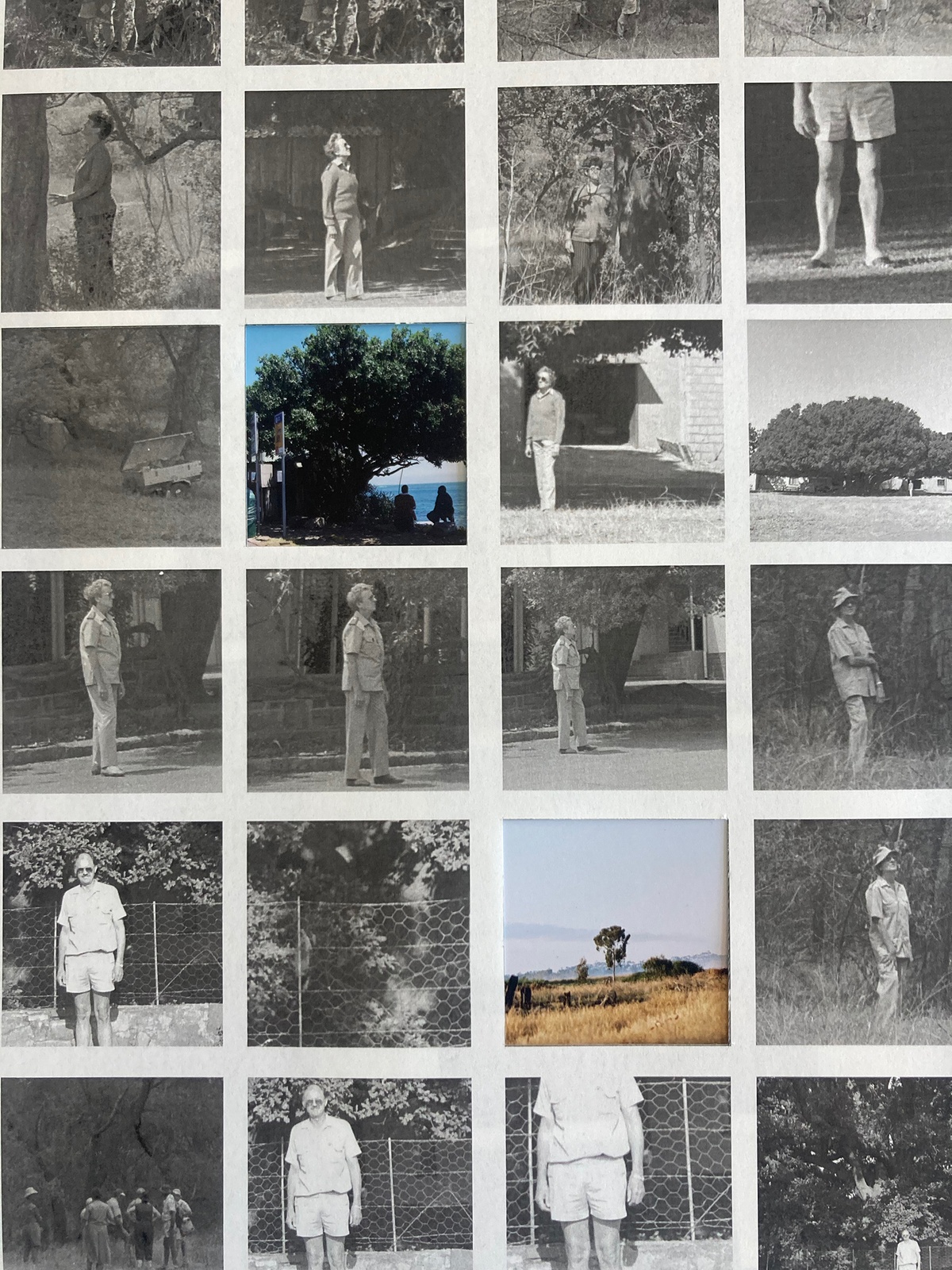

M.T. It’s interesting because, when you look at the stuff in the archive, you can see the working method, which was based on the 12 frames on every roll of medium-format film. They would shoot one roll per tree, as you can see from the negatives and little prints in the envelopes. So that was the method. In contrast, I often photographed trees to fill out a roll. If I’d been photographing some other things, whatever else I was busy with, and there were a few frames left…

L.B. That makes sense. I've always thought of you as more of an observer of the urban environment than a plant person. It tracks that trees might be more of an afterthought.

M.T. I mean, I do like plants, but I'm not a dendrologist. Anyway, that is how my tree pictures came about, not consciously, not whole rolls, but as a way to finish up the frames.

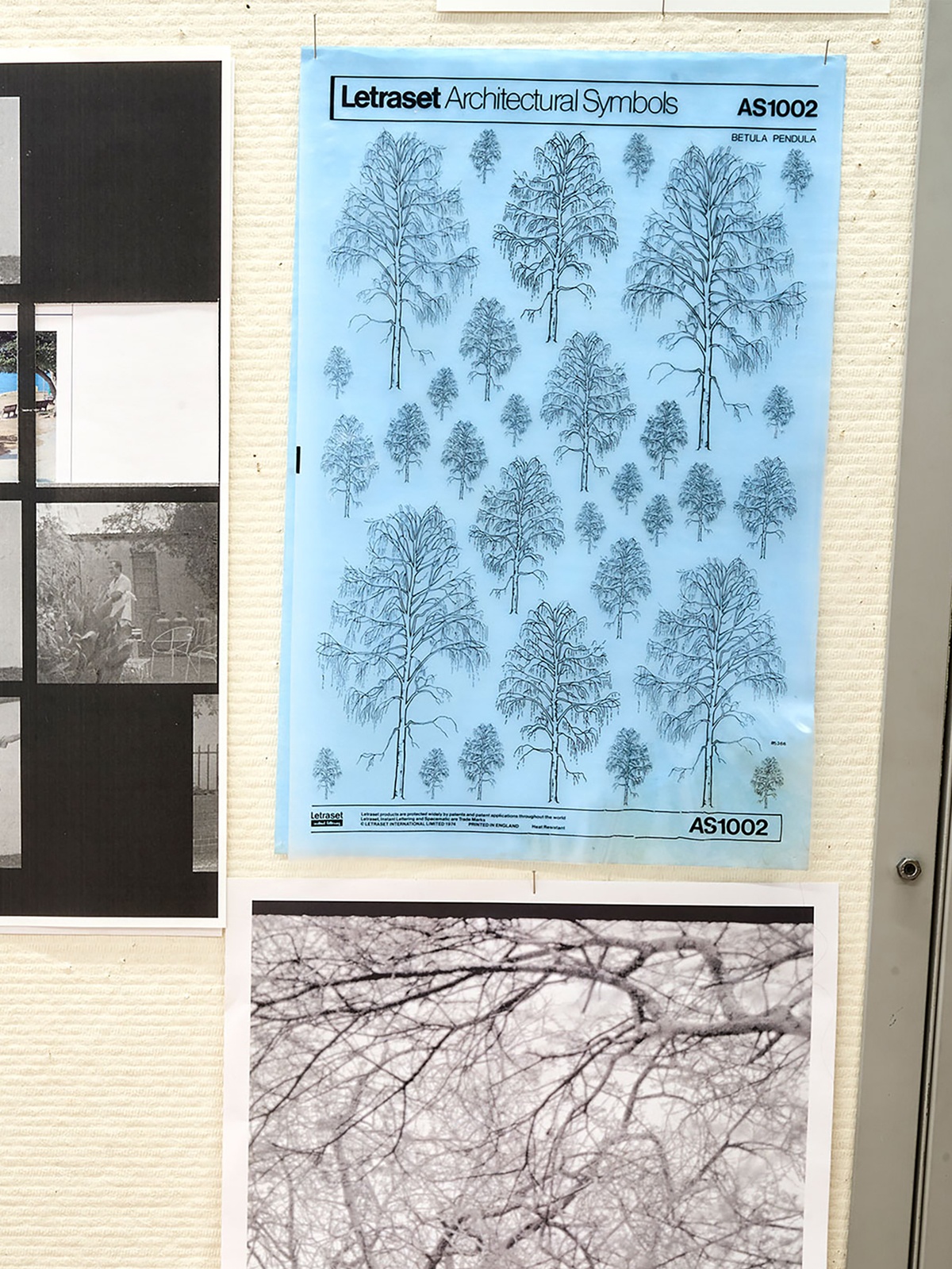

L.B. During your residency at A4, there was also additional material parallel to the photographs at play, like your Letraset forest and an identity plaque from a tree.

M.T. That was all from the dendrologists’ house and offered a way of fleshing out their activities. In addition to photographing big trees, they took it upon themselves to produce name plaques, which you find throughout the country. There was a whole room in the house full of drawers with them. The Letraset that I found – I suppose that's where there is a close parallel to my own training. They would produce graphic material, greeting cards, identification forms, educational material, guides on how to identify and list trees. They were running an entire operation, a scientific operation, which encompassed a lot of graphic and visual activities. There were even paintings – I have quite a lot of paint from them, and pencils. I have some of their drawings and a lot of paper from them. I’m enamoured with the picture-making stuff. When I was looking to apply to universities to study either art or design – and I ended up studying design – I was always most intrigued by the first-year programmes, where you would do a module on photography, a module on painting, a module on typesetting, a module on drawing, a module on scientific drawing. And a decade later, seeing this practice that these people had busied themselves with and all of the tools that they had used was very exciting for me, or attractive –

L.B. How multivalent something as dry as science can be.

M.T. There is a material reality or a material component of their work I aspire to. Nowadays, if you were undertaking this type of work, you would do it with a laptop. A laptop and a phone. You’d maybe flip between Lightroom for the photographs, InDesign for the publications, Illustrator for the drawings, maybe Photoshop. But it would all happen in one contained metal case. Perhaps it’s my age, or when I grew up, or simply what I like, but seeing all these different tools is exciting. Drawing a tree is very difficult and different to photographing a tree, as is turning a photograph into a Rubylith for making reproductions on a magazine cover.

Each part of the process leaves behind artefacts, much like the material I brought into the studio.

I brought it in because I have it, but also because I was curious about it.

L.B. Do you, as the unintended recipient of this partial archive, have some kind of responsibility towards preserving it? Or has the fact that the rest of it has been destroyed release you from responsibility?

M.T. I'm not really that invested or interested in trees – I mean, I can think myself into a place where I'm very interested in trees, but admittedly, it's not where I go – but I do take care of the material that I have. I did hold onto it for years, and I still hold on to it. But I don't particularly feel like it’s a responsibility, as such.

L.B. The information it carries now exists separately from the material. So it’s not a matter of preserving dendrological knowledge.

M.T. I find that the photographs themselves, their photographs, are very compelling. They're very beautiful to me, both in their seriality and as individual pictures. And I don't want to lose them.

L.B. The organisational form that was chosen, with the little envelopes and sloping script, is similarly intriguing –

M.T. All of those different activities of mine intersect in those little envelopes. That’s what you do as a designer: organise material. Responsibility – I wouldn’t say that’s the word.

Several photographers I admire and have had conversations with have spoken about photographs specifically (but I think you can apply this to images in general) as having a charge that tracks events outside their own life or their own story. And that charge comes and goes as things happen in the world. I hold on to them because I feel they have a great kind of potential energy as images or pictures.

L.B. What was the timeline for the inherited photographs? Do you have a sense of when they were taken?

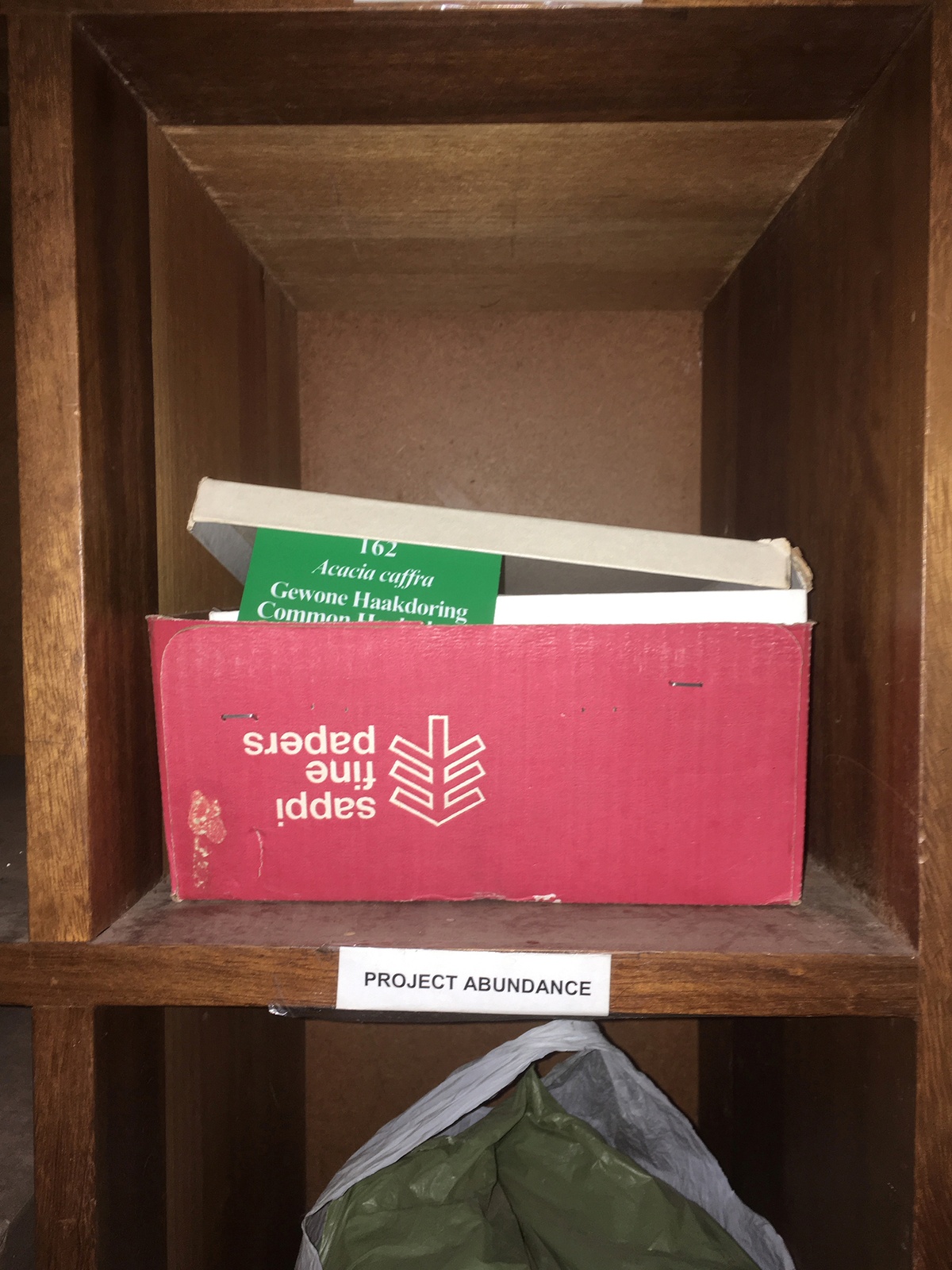

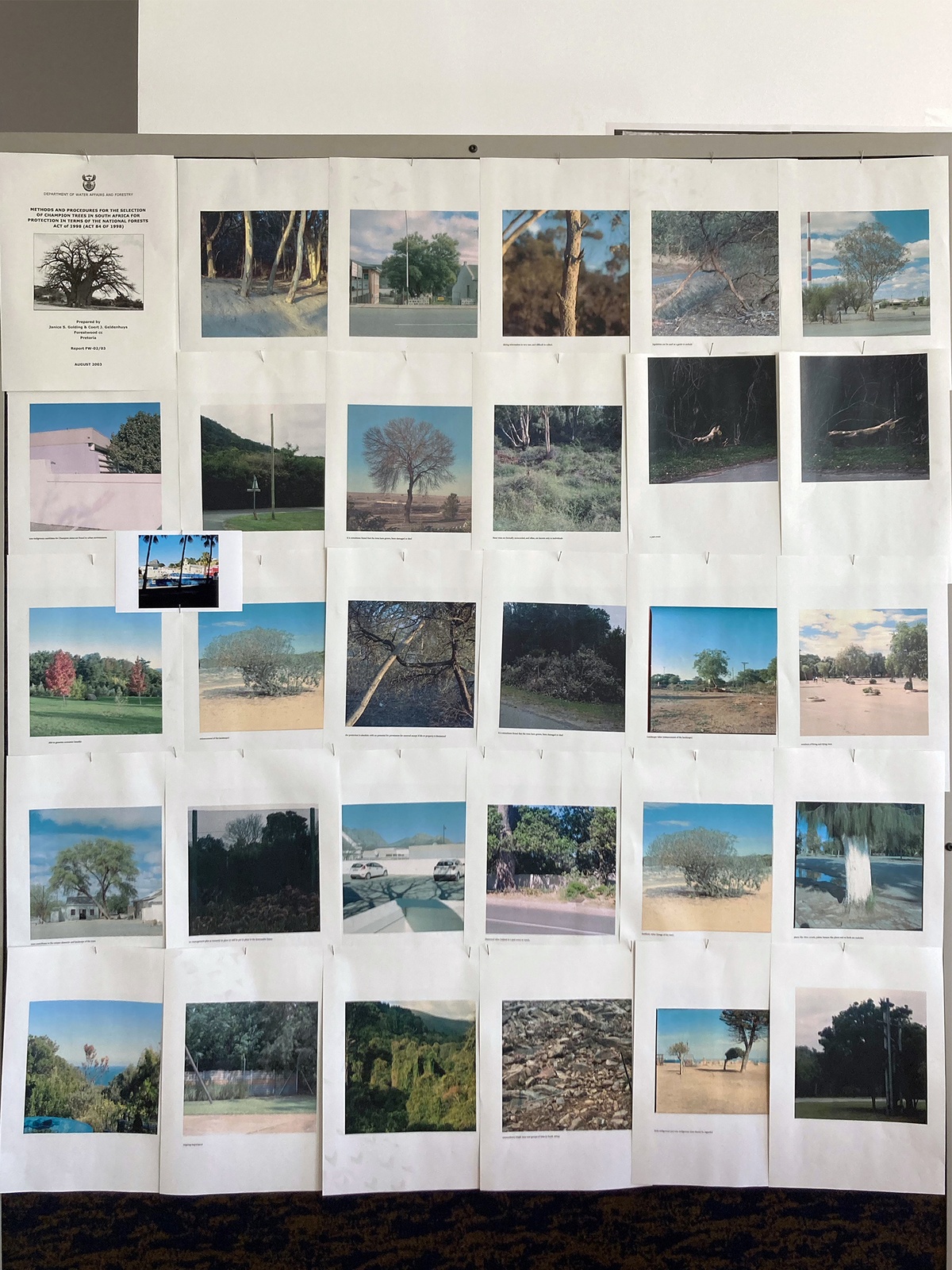

M.T. I do because they are very neatly dated. They seem to start in the mid-80s and end in the mid-90s when the photographer himself passed away. It’s a very interesting period both in South African history and in photographic technology. It’s the dawn of desktop publishing. Digital photography hasn’t really come into the mainstream yet, but the tools are starting to change. That’s the period in which these photographs were made, and they were made for a very specific project, which I only figured out during my time at A4. That’s what the residency gave me – time and space, and the impetus to figure out what these pictures were used for. It seems that they were used for a specific project called the Big Tree Index of South Africa.

L.B. This ties into a question about the literature surrounding the project. The less literary is the 2003 government paper, which you cite in your text-and-image compositions –

M.T. What I figured out while I was at A4 was that the photographs that I’d inherited were used to create a register of what was then called the National Register of Big Trees, which was a project they undertook, I think, on their own volition in that period, so mid-80s to early 90s. This project mimics other dendrological undertakings in other parts of the world where people create these indexes of big trees. I think it's worth mentioning here that dendrology is the study of individual trees, discrete specimens rather than whole geneses or families or tribes of trees. Dendrologists look at the individual tree for its unique characteristics – its height, whether or not it was naturally occurring or planted, and so on. What I discovered in my research at A4 was the National Register of Big Trees – about a decade later in the New South Africa – is cited in a piece of legislation produced, I think, by the Ministry for Forestry (or whatever it's called now, or was called then, the Department of Forestry and Environmental Affairs). In 2003, that department in the new dispensation drafted a piece of legislation formalising the state's relationship to these big trees. That was the link. The archive I had inherited was created for this tree report, for this National Register of Big Trees, and the National Register of Big Trees became the bedrock for this champion tree legislation. I forget the title of the paper –

L.B. It's interesting because I had this idea that many of these threads were already being followed in advance of your residency at A4, if only because it unfolded so quickly. But actually, it was just precipitating in the studio. It happened here.

M.T. Well, as I said, I had time and space.

L.B. It wasn’t a particularly extended amount of time, though clearly generative regardless. Here’s the title: Methods and Procedures for the Selection of Champion Trees in South Africa for Protection in Terms of the National Forest Act of 1998.

M.T. Yes, these photographs were part of creating a framework, which then morphs into that piece of legislation. Is that interesting? I think so.

L.B. And then, just because it’s on the table as we speak, I’m curious to know if Sixty-Six Transvaal Trees formed part of the inherited archive.

M.T. No – but just before I began the residency, my godfather was down visiting my parents. It was probably a week or two before I came to A4, and I asked him, where does your interest in and love of trees come from? And he mentioned that, as a young man, this book, Sixty-Six Transvaal Trees, was published and given to him as a birthday gift, which sparked his lifelong interest in trees.

L.B. It offers a keystone to the acquired archive –

M.T. That book was not immaculately conceived. It slots into a political reality.

L.B. Would you say the same of the giant tree project?

M.T. I mean, it does get accepted into the new democracy, though it was produced in a very specific political period: State of Emergency, mid-80s.

The project and the author’s life terminate at the beginning of a new political dispensation. But their work finds itself useful regardless. If you look at the photographs themselves, you can read them as part of some sort of colonial aesthetic. Little people in short pants – all white – standing next to trees. There's all of this note-taking and organising and typologising and dating. All of that happens, but the effort is useful. It finds another charge, right?

L.B. Does Sixty-Six Transvaal Trees have a more apparent nationalist bent?

M.T. Very vaguely. The national ideology of the time is reflected in the presentation of the book itself, as opposed to the material. The name, the allusion to the South African Republic, the fact that it was published in 1966 to mark the fifth Republic Day. But the material, the actual content, is very dry, very scientific. It's all this thing grows well here, this thing doesn't. It's not like this tree represents our national aspirations. It's none of that, really. It's much more botanically minded. I imagine someone was just really good at getting funding for their project. But then again, you can't divorce these things from each other. There is definitely a human impulse to understand the world around you as a way, in part, of asserting dominance over it. Historically, in South Africa, this commanding of nature, this desire for knowledge, might be framed as protective, though it serves this second function too.

L.B. I have two last questions – the first asks after collecting in your practice. Is there a working logic you follow? A wider project of seriality? I suppose what I’m asking is whether you accumulated photographs – those you’ve taken – with a strategy in mind, even if it’s not necessarily towards anything in particular.

M.T. On a bad day, the accumulation itself freaks me out. I don't like it; it reminds me of my father. Just too much stuff. Can't throw anything away.

But things become interesting in the company of things like them – you can start reading them differently. You can start picking out patterns and finding narratives and coincidences.

And tracking change. Photography lends itself to seriality. You can stand in front of the same thing and make 36 pictures of it. Each one of them will be different. This is very difficult to do with painting or with drawing. It's inherent to the medium of photography. You can reproduce not only prints of an image, but you can actually reproduce the conditions of making an image. You can stand in front of the same building once every five years and make a picture. It's simple if you remember where you stood. So accumulation is more a part of the medium than my practice. That said, I am attracted to serial work – very taken by Ed Ruscha, as I said earlier; Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant’s train graffiti in 1980s New York, an early influence for me. As was my father’s work, I suppose.

With my own pictures here, I don’t think I was doing that. I do that with some of my other photography projects, which don't really exist anywhere. But the tree – my own tree pictures – were not that. I mean, I've done serial work. As I've mentioned, I've done trains, the bank buildings.

L.B. A more conscious collecting –

M.T. A structured project, much like the archival material. It's done for a reason. People know what they're looking at. With the other photographs, I –

L.B. Just see what happens.

M.T. I mean, I do like trees, obviously. I like the way that they look. They do things with light and shadow and colour, which I'm attracted to. They also serve as interesting markers of time. You can always tell the season from a photograph of trees – and place. And if you start scratching and thinking about things a little bit more, there's plenty to read in them, and I like reading.

Trees are a useful stand-in. They’re alive; they have a presence.

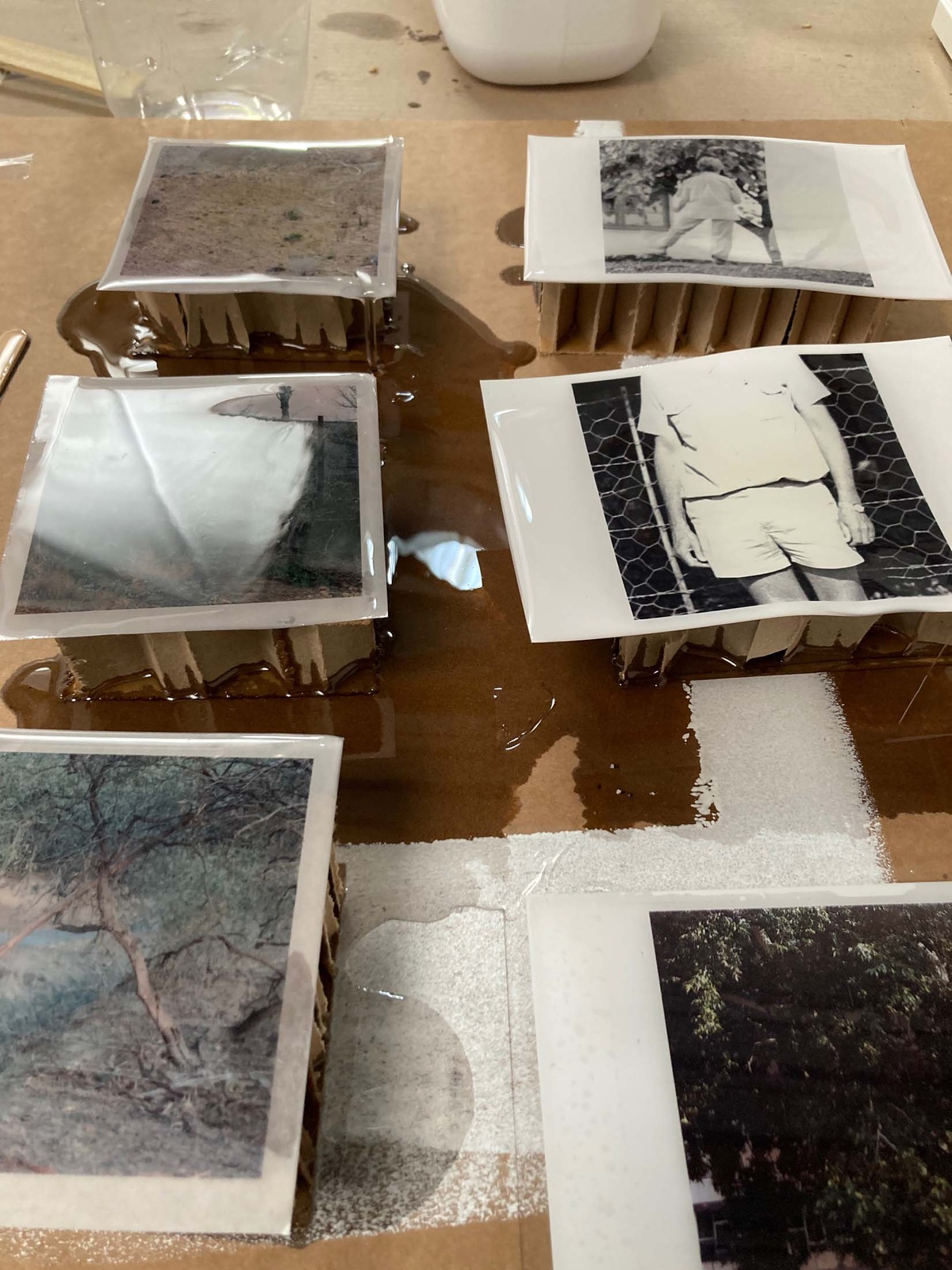

L.B. I also wanted to ask about your experiments in making image-objects. During your residency, you spent time at Atlantic House with Jared Ginsburg, working and playing with resin. Could you follow that thought for me?

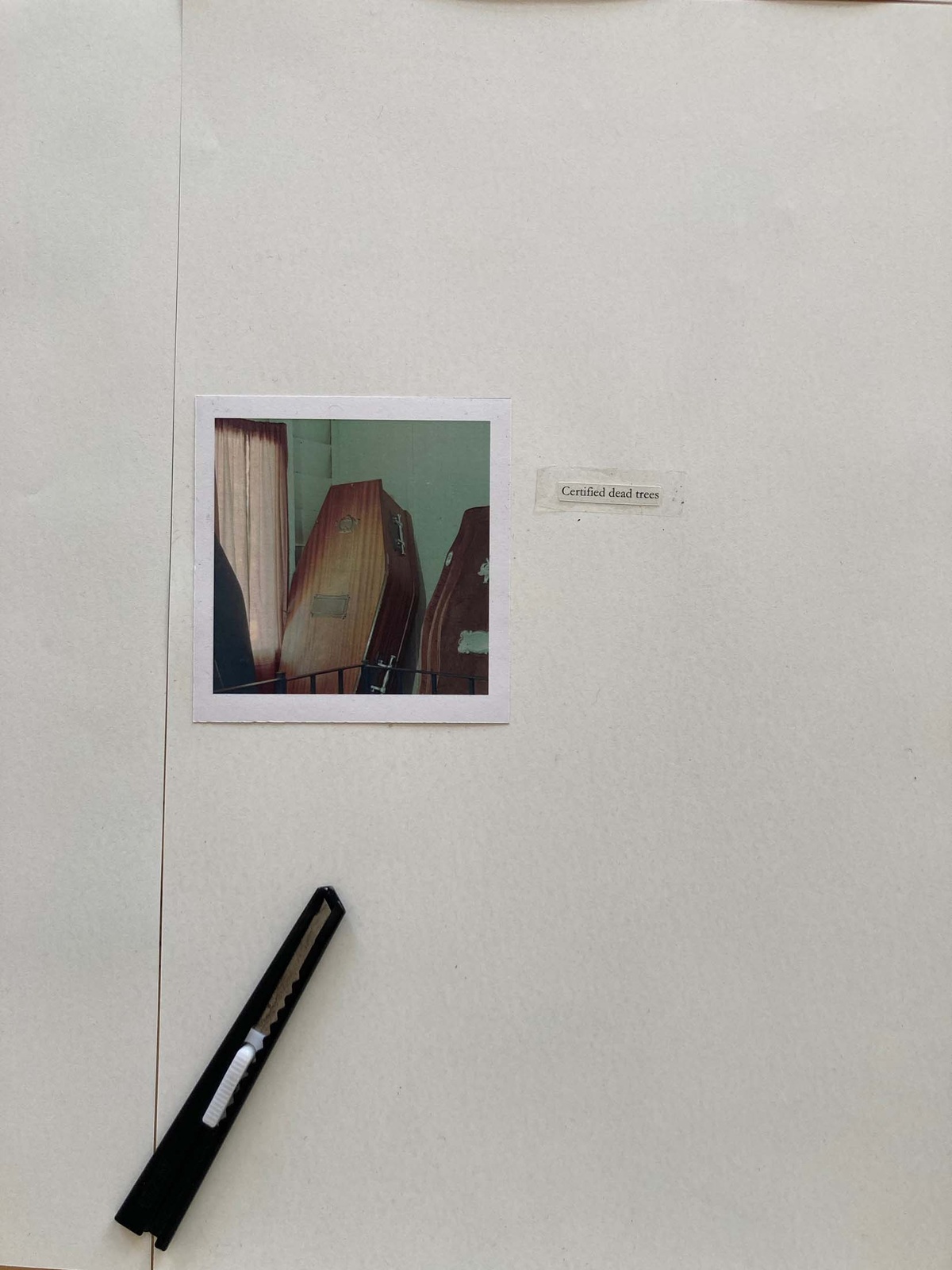

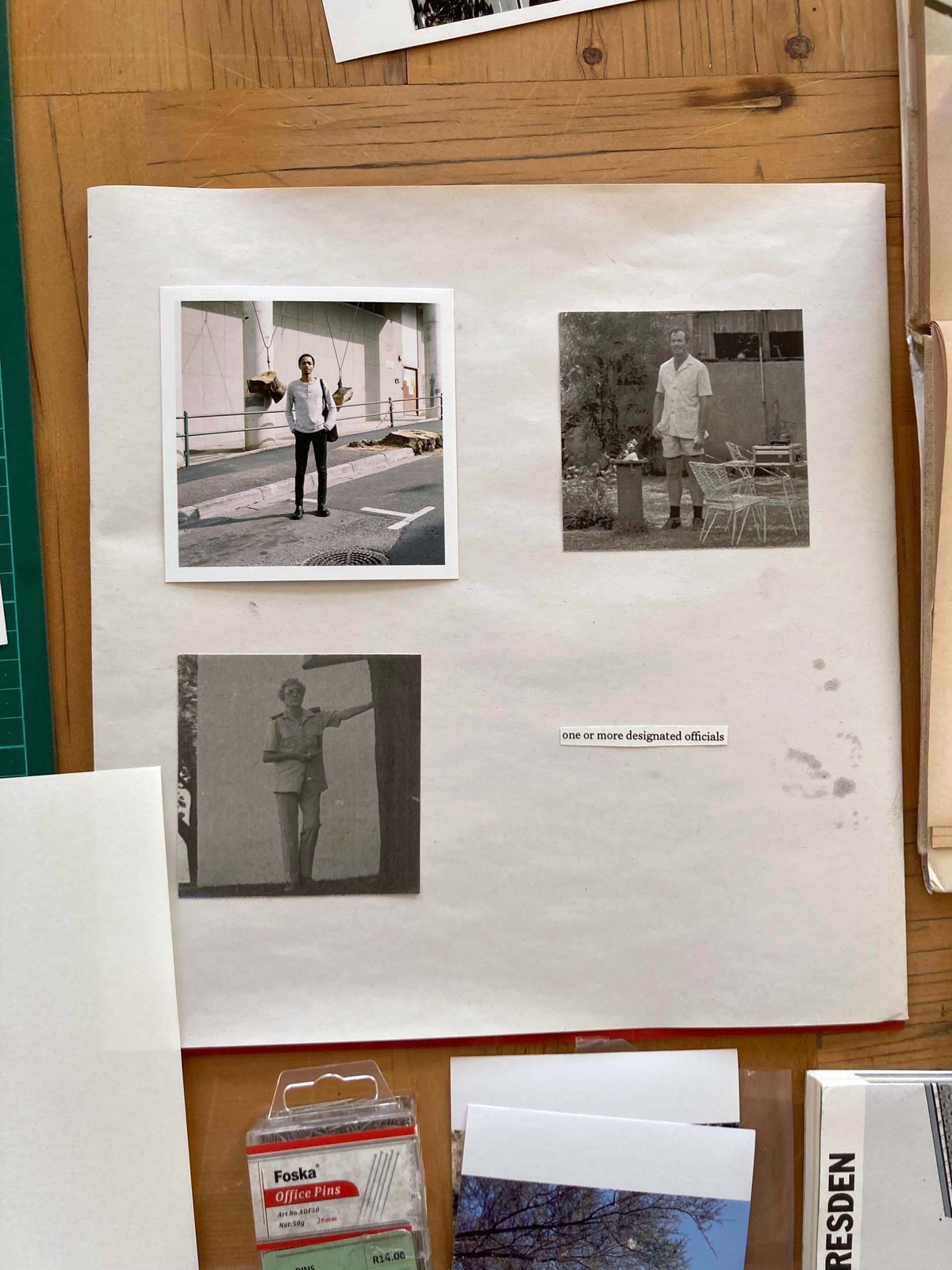

M.T. That began in dialogue with the archived envelopes. Honestly, I think we're all very taken with those little envelopes, with the way they exist as objects rather than photographs or reproductions or books, the ways in which you’d usually engage with such images. The envelopes are novel. Everyone falls in love with them. They combine image, text, ground – the ground being the envelope itself – and information, the facts sheets that are filled out. The experiments at Jared’s studio, which only happened in the last day or two of my residency, were an investigation into how to join image and text together, which is something I do a lot as a designer. Usually, this is purely graphic and done in InDesign. I was looking at other means of joining text from the legislation with my own photographs. How could I put them together? All the time, I was thinking about these envelopes. Because my photographs of trees are not serial, I don't have 12 pictures of each. I realised early on that's not going to work.

I cannot mimic the archive; I don't have that seriality, which is part of what makes these pictures – these objects – appealing.

With every envelope, you can see, oh wow, it's a little series. It looks like a Bernd and Hilla Becher project. Instead, I had pictures, I had words, and the question was how I might bring them together –

L.B. In a unifying object.

M.T. I think it's worth mentioning Iñaki Bonillas, who I met when he was in residency at A4 in September last year. I was very energised by his practice. In recent years, I think I've gone a little… I've gone off photography. You can do the photographs on the wall behind museum glass, and you can do the photobook that you publish with Steidl – if Steidl wants to publish your book. But in between that and Instagram, there's not much middle ground.

L.B. And the exhibition strategy when it comes to photography tends to be very sombre.

M.T. Especially here in South Africa. We have a very strong photographic culture or heritage, or whatever you want to call it – organism, life form. And photobooks are difficult and expensive to produce, even harder to sell (rest in peace, Fourth Wall Books).

L.B. It's a very finished form. What was intriguing about what you were doing in the studio was the sense of a provisional engagement with images. It didn’t have the finality of going to print, of persisting in a given state for the rest of time.

M.T. I've been painting for the last six or seven years now. And in painting, other parts of me come through. I can't draw a straight line for the love of God. There's something in my hands, in the way that my hands make things, which I recognise and feel at peace with, a sort of clumsiness. I’ve often wondered how to get that across in photography, how to make that imprecision apparent. There's something non-authoritarian in my own hand. It took me years to make peace with my clumsiness. And I'm interested in that. I was looking for ways of working with photography where I can – maybe clumsiness isn’t the right word.

In photography, there is a remove: I'm just standing here, I'm looking, I'm gazing, I'm judging, documenting, recording. I'm not involved. I'm panoptic and robotic. I make my scans, and they’re perfect, and then I print little books, also perfect. My hands are absent. I’m always at a distance.

I started painting because I became very uncomfortable with that distance – I didn’t want it, and I didn’t really get anything from it in terms of a practice. Now I find I'm more interested in photography again.

L.B. You're reintroducing yourself into the image much like you can with painting. You're reinstating your sensibility.

M.T. Despite the fact that all of this stuff is shot on film, I don't have any darkroom chops. I'm not out there printing things, dodging shadows. If you read about or talk to older photographers, you realise how much of that subjectivity of making came through in the darkroom. Adjusting a histogram in Photoshop just doesn't do it for me. There's no finality to your actions.

L.B. You’re not bodily involved in the outcome.

M.T. In the studio with Jared, I would pour resin over the photo, and that was it. I couldn’t make corrections. I’m of Greek descent; I have a lot of body hair. It gets into everything. If a hair falls into the curing resin, too bad, that’s it. They're all over my paintings, and I hate it.

What I liked about having only one chance with the resin was that it focuses you. You're very present in the making. And that's something I seek. And which I get when I’m making photographs in the field, a sense of hyper-presence. I'm here. I'm concentrating, I'm looking –

especially with a Hasselblad because you look down at the picture. I'm interested in edges, in painting and photography, in what happens at the edge of the frame. When I’m composing a frame, I really pay attention there. But, you know, once you've done that, once you’ve pressed the button, aside from sealing the roll and licking the little sticky part shut before you take it to the lab, that's it in terms of needing to be really focused and precise. I guess if you're doing scans, you're trying not to get your fingerprints all over them, but that's just a pair of gloves.

I don't think the resin was the most interesting thing I did here. I didn't feel so good about it, to be honest. I could see what I was trying to do; I was trying to work back to the envelopes, and the envelopes were still more intriguing.

L.B. I find it curious that you were inviting chance and imperfection into a discipline that is otherwise very perfect.

M.T. And I was working with my own photographs and pairing them with the legacy of the archival photographs, with the legislation they had produced or influenced.

L.B. And perhaps follow a more humorous thread, which is wholly absent from the original images –

M.T. I don't know if humour was entirely what I was going for. I mean, I wasn't really trying to make jokes… Then again, sometimes I was.

L.B. There’s the humour of the non-sequitur, the oblique links between word and image, the visual puns –

M.T. There's something very abstract about legislative language, which I'm fascinated by, how it holds both specifics and vagueness, a vagueness you don't find in such a concentrated form almost anywhere else in English. But when you read legalese, when you read laws, they're extremely particular and extremely indefinite, open to interpretation, open to commentary – open to play, actually. This is what happens in court. People play. They really drill down into the meaning of things. And it's often absurd. I was listening to a podcast about some historical event – a piece of legislation was passed in French and later translated to English, and a successful challenge was made because of the lack of a definitive article in the English translation. As a result, a whole country was invaded. And that's all on interpretation. We’re pretty far down a rabbit hole here, but I'm interested in that and have been and probably will be for a long time.

L.B. Before we end, I want to ask you about scale. You enlarged some photographs in the studio – your own and those from the archive. I’ve always been more drawn to the diminutive, and I think that’s one of the reasons so many people are absorbed by the envelopes; they are small, they hide information, both in their scale and their form. Did you make useful discoveries when you enlarged their images?

M.T. The enlarging was a different game that I was playing. I think a lot of what happened here was playing games –

L.B. Making opening gambits –

M.T. Setting rules, seeing what I could do with one or both of the archives. What I was doing with the enlargements – and I’m not sure it really came through in the presentation – anyway, I would make a scan of one of the negatives from the archive and then find the accompanying fact sheet, find the diameter of the tree, and reproduce the width of the photograph to match the measurement given. The width of the image is the width of the trunk. So you can actually get a sense of the thing in the picture from the thing, which is the picture.

When I look back to the work that I made, I think that was a more successful game than maybe the word-and-image pairing because the pairing sometimes came off as a bit too smart.

Some of them had a better poignancy; they were either more absurd or more referential, or the dialogue between the two parts was stronger. They became hierarchical in a way. You could say this one's better than that one, whereas this measuring game was far more horizontal. You could work through the entire archive in this mode.

L.B. It follows a more scientific logic –

M.T. But also a picture logic. And a reproduction logic, which I like. How big do you make a photograph? You can make it as big as you like.