K.M. It was 2011. I went with a couple of friends to go get a printer in Johannesburg – we had this idea to make merch for things and make publications, and part of this was to drive all the way to Johannesburg to fetch a printer. On the way down from Johannesburg, just before Mossel Bay, we landed up at the Beervlei Dam. It’s more of a flood barrier for the Grootrivier than a holding dam. It fills up every fifteen years or so. I took a photograph, and it was there that I had the idea to make a project about dams.

J.G. Did the project appear immediately to you as an intersection between hard architecture and the landscape?

K.M. I can say that it was a pointed moment that still stands out to me. It occurred in that landscape, right there, as I was experiencing these manmade things in the natural terrain.

J.G. I have a photograph of two trees that you took – I think it’s also from that same trip.

K.M. Yes. And there were other trips that led to that trip. I had been assisting Dave Southwood while I was at Michaelis and still studying photography and he had come to do some lecturing. I started working for him part-time and we would take these trips around South Africa and during these I also did some of my own shooting. That’s when I made the switch to the sculpture department – I realised I could work for Dave and continue on with photography that way, while getting the input that I wanted from Jane [Alexander] in the sculpture department for my last two years of studies.

Since photographing that first dam, some of the trips that I’ve taken have been targeted towards the dams, and some of have been taken while en route to somewhere else. I think there have been about ten trips in total. A couple of them I’ve taken together with Andrew Gilbert, who is interested in war memorials in South Africa, and we figure out the route together to include those sites and the dams.

These trips are like a history lesson, travelling with someone who isn’t South African but has learned all about the conflicts of this place.

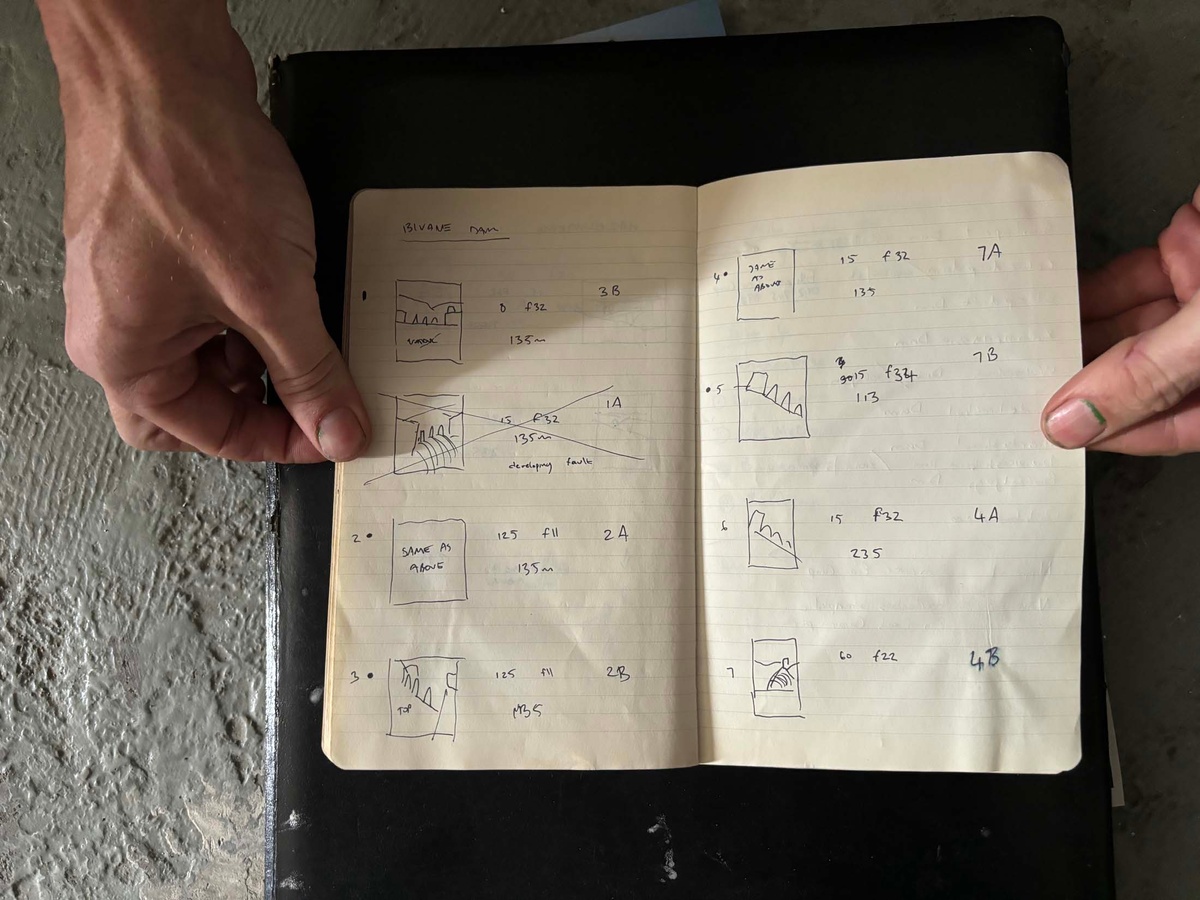

We’ve done two trips that are focused on provinces predominantly. Three years ago, we did Kwa-Zulu Natal, and before that, the Free State and Gauteng. The planning is intense before that as we mock up the easiest route because some of these places are really wild to get to. The photograph of the Tierkloof Dam near George, for instance – it took us about three hours to get there along a restricted road that’s reserved for controlled fires on the mountain: a real mission.

These are National Key Points, they are resources, sometimes they are patrolled in a way that means that no one is interested in you being there. We visited Kwa-Zulu at the time of the uprising and the guards we encountered were really on edge. This requires a more covert operation with very limited time. But others are almost completely derelict and feel abandoned. You jump a couple of walls to get the shot and there’s no one around.

D.M. Do you have to time your arrival with the light to get the shot?

K.M. Sometimes you can sit the whole day on one site and see the light change, but most of the time, you have to get going. I shoot about two or three dams a day but it would be great to have a whole day with a dam.

I’ve never arrived and not been able to take a photograph. For instance, it has never rained when I’ve been out there.

Limited time is also good, you get there and take the photograph and leave: limited time gets you to do what you need to do.

J.G. Have there been times when you’ve met interesting people?

D.M. Or times where people are intervening in the shot and you need to wait for them to leave?

K.M. Only twice have I met people who were keen to show me around the dams. Coming down the N1 to Calitzdorp down the Swartberg Mountain Range, I’d been put in touch with a guy called Fox. I messaged him about two days before, but there’s no signal where he is. He went to town to get his supplies and he got my message. He sent me GPS coordinates. I arrived and he was completely surprised, but in a good way. For some reason, he had been expecting a child, a ten-year-old boy travelling around with his parents doing a school project on dams. He was so kind, giving us free reign to walk around the tunnels, the turrets, to stay as long as we wanted.

The only other time someone has been eager to take us around was in Buffelshoek. I guess I’d say he was the dam keeper.

J.G. Like a lighthouse keeper.

K.M. I suppose so. The caretaker of the dam.

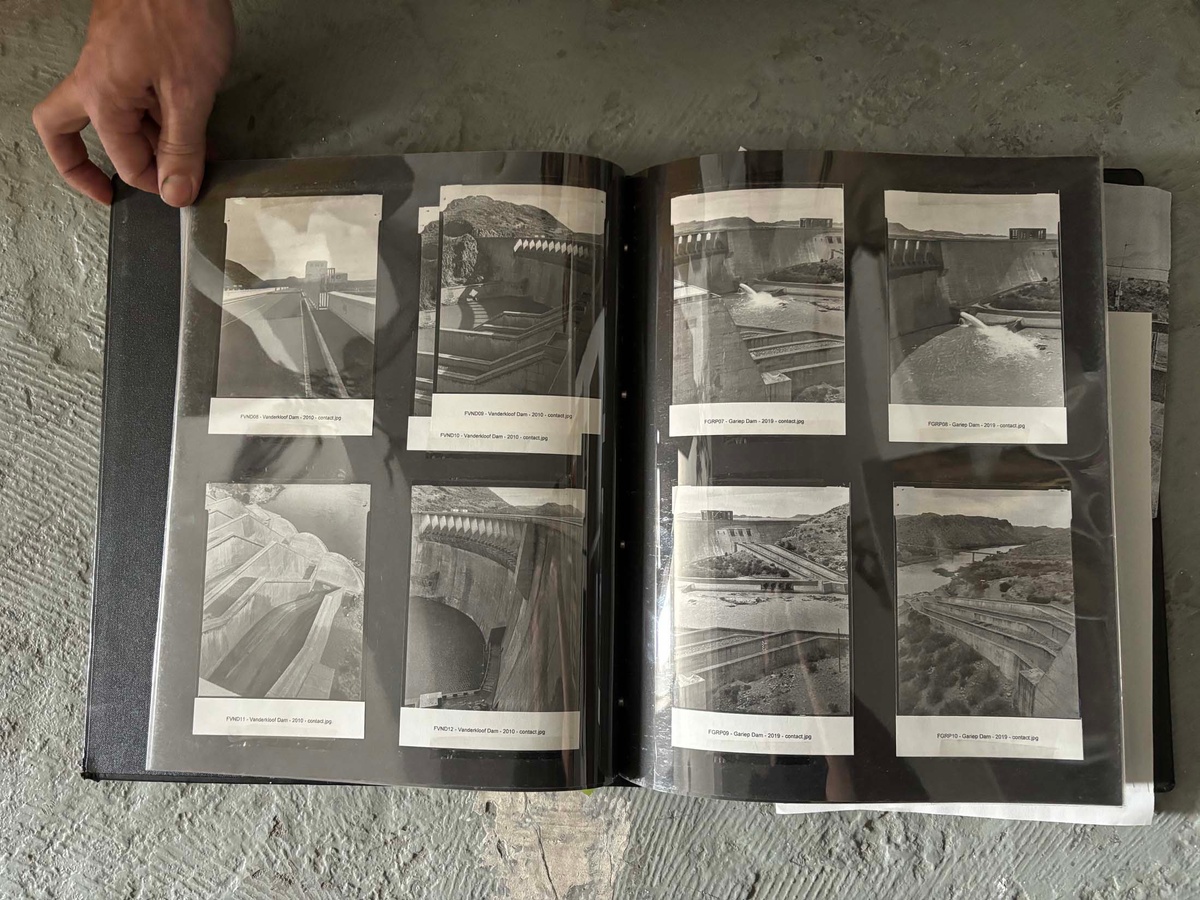

And also, only twice have there been other visitors around a dam. The large dam inside the cover page [of Dams, 2024] is the Hartbeespoort dam: that’s a tourist attraction and you can see the people visiting the dam in the photograph. The other ones that are publicly accessible are the Van Der Kloof and Gariep dams – otherwise there’s never other visitors around.

S.d.B. Is it loud? Looking at some of the images, you feel you can hear all that sound.

K.M. Yes. When you’re walking below and you look up, you’re very aware that there’s a wall holding up all of this water above you, a wall between you and all this energy. And sometimes, the lens gets misted up – you find yourself inside a cloud of water vapour.

S.d.B. Rivers are deployed as a metaphor for time and transformation: you can’t step into the same river twice, and all that. Dams try to shore up time, or control time’s passing, if not stop it completely. There’s something about time and the action of taking a photograph.

K.M. When there are controls around, these are very controlled environments. There are reminders everywhere of health and safety checks.

[Note: Kyle shows us some images he’s taken in what he refers to as ‘the studio’ portion of the dam environment, the places where work happens – green signs with ‘Think Think Think Think’ written on them, and the translation into Afrikaans ‘Dink Dink Dink Dink.’]

J.G. The photograph of the dam with the tree feels like an anomaly.

K.M. The dam with the tree is called Misverstand Dam – a mistake dam: there was some confusion between what the farmer thought the size would be and its eventual size. It’s a tiny dam.

The forms of these dams are derived from the context in which they’re situated: the bedrock, mountain, terrain, and substrate beneath it. So that the way they come to look is directly related to their environment. When you frame up the image, you don’t have free reign.

You’re constrained by the shape of the land and the design of the dam: where you can put the camera, how you can approach it.

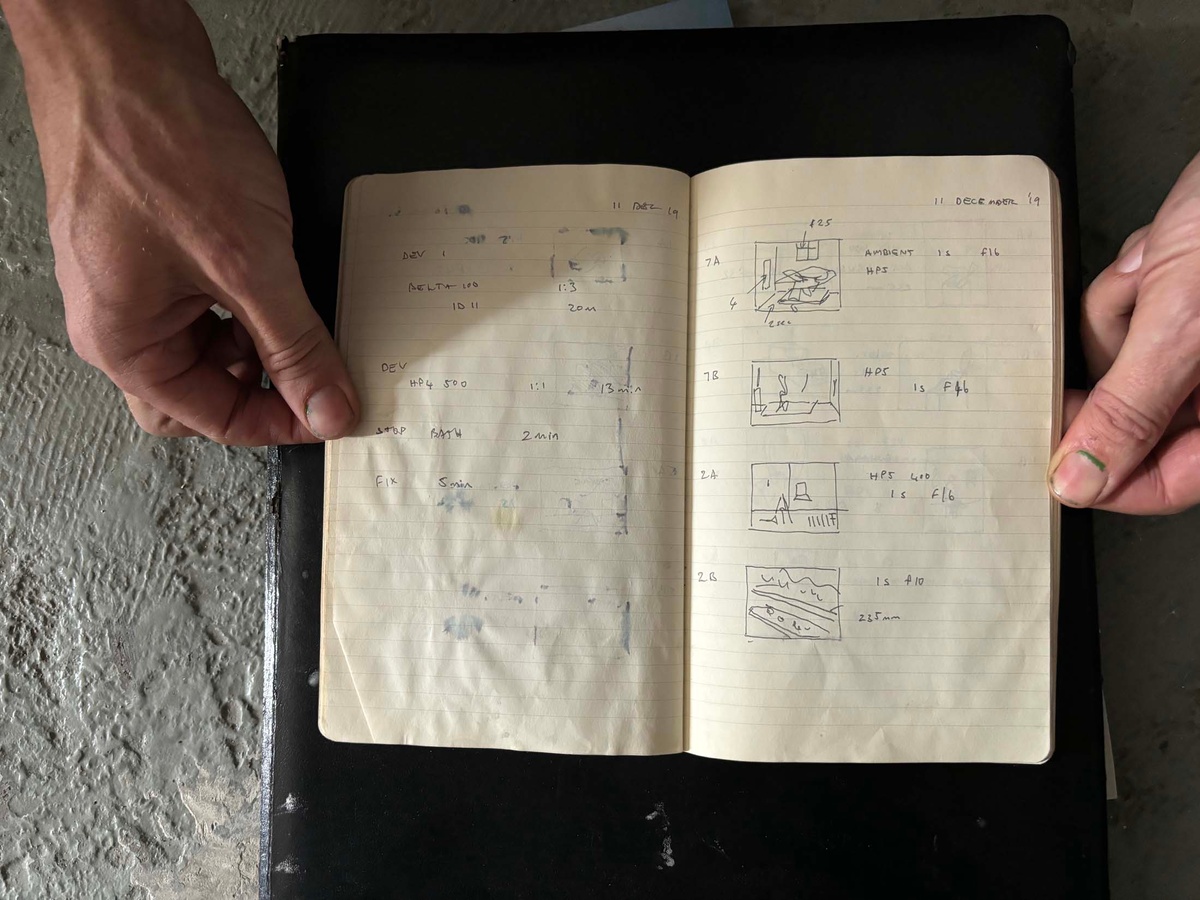

I shoot portrait as opposed to landscape in 4x5. It’s a portrait of a dam in a landscape rather than a landscape photograph.

I’ve learned to measure twice, cut once. So much can go wrong along the way. At the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, I took only three images at the site. It took days to get there.

D.M. Are the photographs of the dams related to your sculptural works?

K.M. They aren’t deliberately in conversation with the sculptures. Maybe the dams are a resource for the sculptures…maybe.

S.d.B. Can we talk about the camera?

K.M. This camera is purely mechanical; this means you have full manipulation of what you want to do. You control the perspective. Imagine you’re in the car, looking up, and through the camera you’ll see these parallel lines that taper to a point – this camera allows you to control the perspective, to limit the distortion, and to get everything in focus from the foreground to the back. You could make everything look like a model, where the whole world looks miniature. I find that a bit gimmicky. You tilt your lens in relation to your film.

J.G. Looking at the water in the photographs – the flows, the choices you’ve made in relation to where the water is moving and where it’s still – the water must be hitting the ground below with such force.

K.M. When capturing water, the flow of the water itself: do you want to freeze the moment of the water flowing? Do you want a longer exposure where you’re getting the motion of the water?

The spillways are built to anticipate the future because the force of the water falling from the outlets mustn’t cause future erosion down below.

D.M. What scale do you imagine these photographs being printed at?

K.M. I always imagined I’d print them out big, where you can see all the details of a handrail, and there’s a sense of the human interaction with the scale. But over time, in my imagination of how they’d be printed, they’ve gotten smaller and smaller, more intimate.

I think there are 234 dams in total that I want to get to – these are concrete arch dams, not farm and earth embankment dams. At some point in time South Africa was one of the top dam producers in the world – this was between the 50s and 70s. You’ll come across those dates engraved on the infrastructure, on all the roads and the dams somewhere in the 50s to the 70s. Only ten dams on the list are built since 1994; all tiny ones. So this is a very long-term project. We’ll have to see.