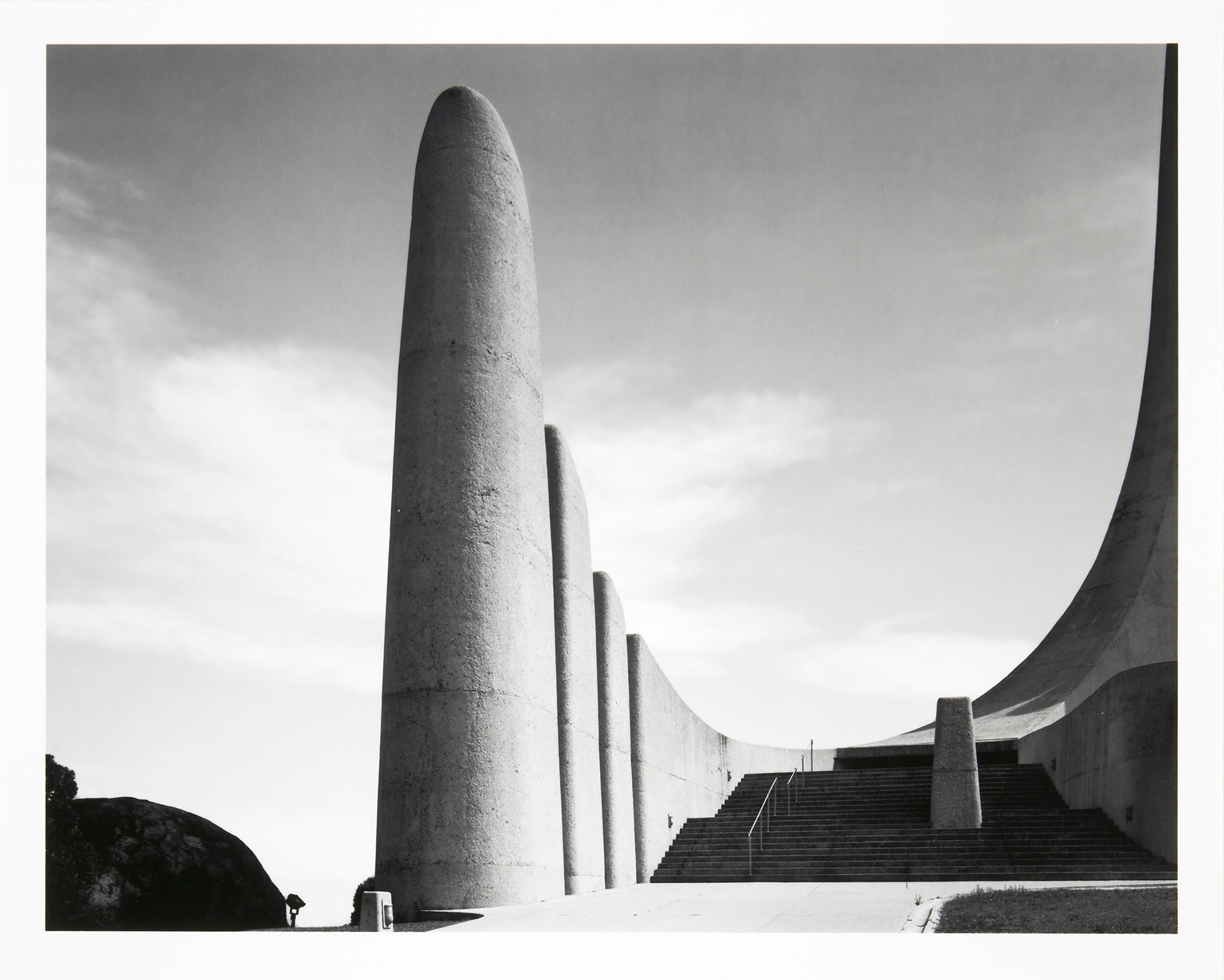

Public monuments are instruments of public instruction. They delineate national retellings of history, offer physical metonyms of select narratives, in turn commemorate and celebrate events of assigned significance.

In form and content, they are variable. A monument might champion the lives of esteemed individuals in bronze likenesses, personify virtues and emotions in marble, or assume more spatial expression in civil architecture and urban interventions. Some aspire to ambivalent abstraction; others insist that the weight of a life find an equivalence in the weight of metal or stone.

Central to the monument’s mechanism, regardless of its image, is the insistence: These things we remember; these things we value most. This we is revealing less of collective sentiment than national imaginaries of a preferred public. That monuments at once affirm shared ideals and ideologies, and flatten difference, is a failure necessary to the form.

Dissent, subtleties, complexities – such things are not easily expressed in static sites shaped by oversight committees, made to appeal to a large, and largely nebulous, us. Folded into this collective first-person pronoun is the tacit acknowledgement of a similarly ambiguous and undefined other – them.

But stories of nationhood change. Retellings are revised; new dispensations look to new narratives. Monuments of the past slip into irrelevance, becoming benign landmarks at best and malevolent vessels of disavowed histories at worst. That they are more often made of hard, immovable matter – metal, granite, brick-and-mortar – precludes easy revision of their image.

Plaques might be reinscribed to reflect changing attitudes, revised stories given to old objects, and others left to persist in obscurity. For the most part, public monuments are not easily removed. But they are removed, from time to time, by municipal order or fate.

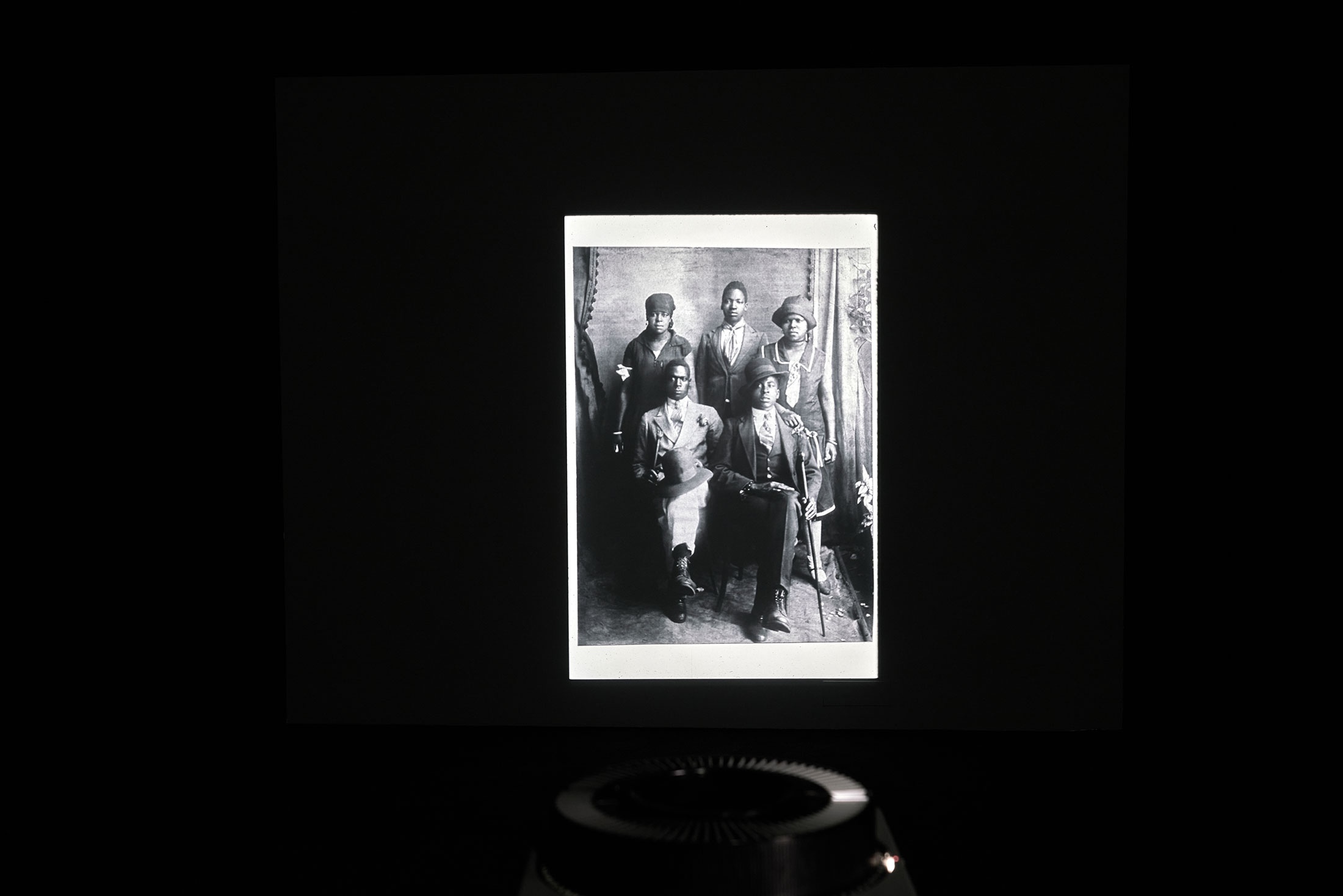

Attending every public monument and its pat rehearsals of the past, are the less ‘usable’ histories of unaccounted, individual lives. That these retellings might come to inhabit buildings and objects designed to serve conflicting or only tenuously related accounts introduces an unanticipated liveliness into otherwise staid vessels.

Whatever the architect or sculptor’s intention, the commissioning brief, the state-mandated story to be served, these other stories crowd in, too. Covertly, incidentally – like so much dust in the brickwork or the slow patina of time against the lustre of polished bronze.

Symbols travel – monuments from other places come to stand as their metonyms. Idealism transmits like sound through water: far and indistinctly.

Reduced to icons, monuments proliferate as signs, becoming tools of political soft power and cultural imperialism. All those fridge magnets, those many postcards, a million photographs across our digital devices; an image made for export. Where we might remain sceptical of our own national monuments, or fail to notice them entirely, we are quick to imbibe the promises of others.

But what of those incidental monuments? Where the word ‘oversight’ shifts in meaning from ‘overseeing’ to ‘a failure to notice’. An unfinished overpass, a disused factory, an empty landscape – might such things also assume the weight of monuments?

Those scenes in which the past is insistently present, however benign they might first appear. Ambivalent images, coloured by their historical significance and heavy with silence, all the more poignant for the absence they picture. A photograph can be as leaden as any cast statue.

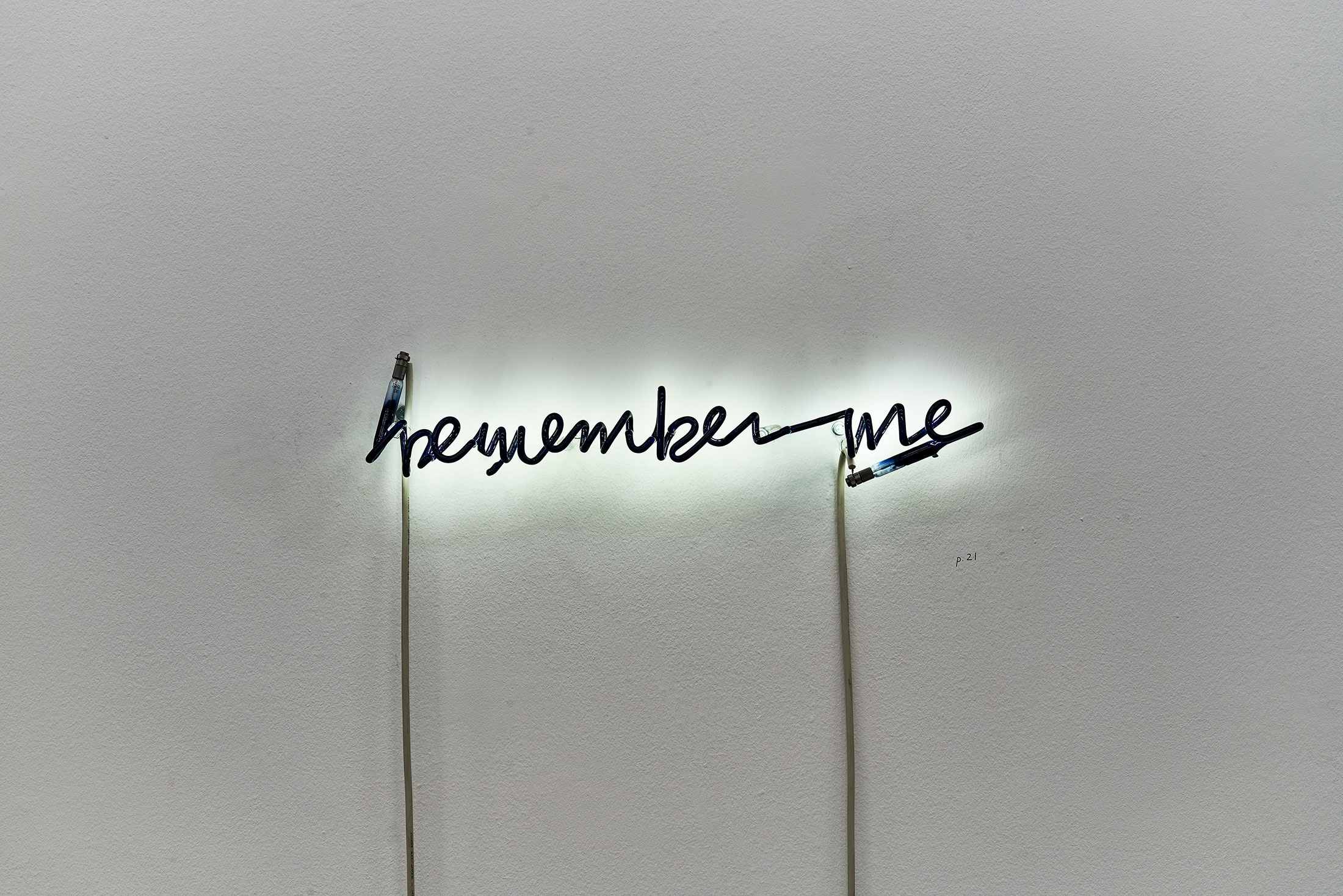

Look to the smaller monuments – to the traces that attest to individual lives. Excerpted from the world, they become objects of quiet contemplation.

They might be diminutive in scale or humble in medium, might recall only the most commonplace of actions, but they continue to resonate beyond the life they describe, transfigured as testament to less publicly lauded but no less valued ideals: commitment, care, ordinary devotion.

Such monuments, called out from obscurity, offer something other than textbook histories; they are less instructive than redemptive. Beneath the narration of nations, these unwitnessed and unwritten stories pass like currents below the still surface.

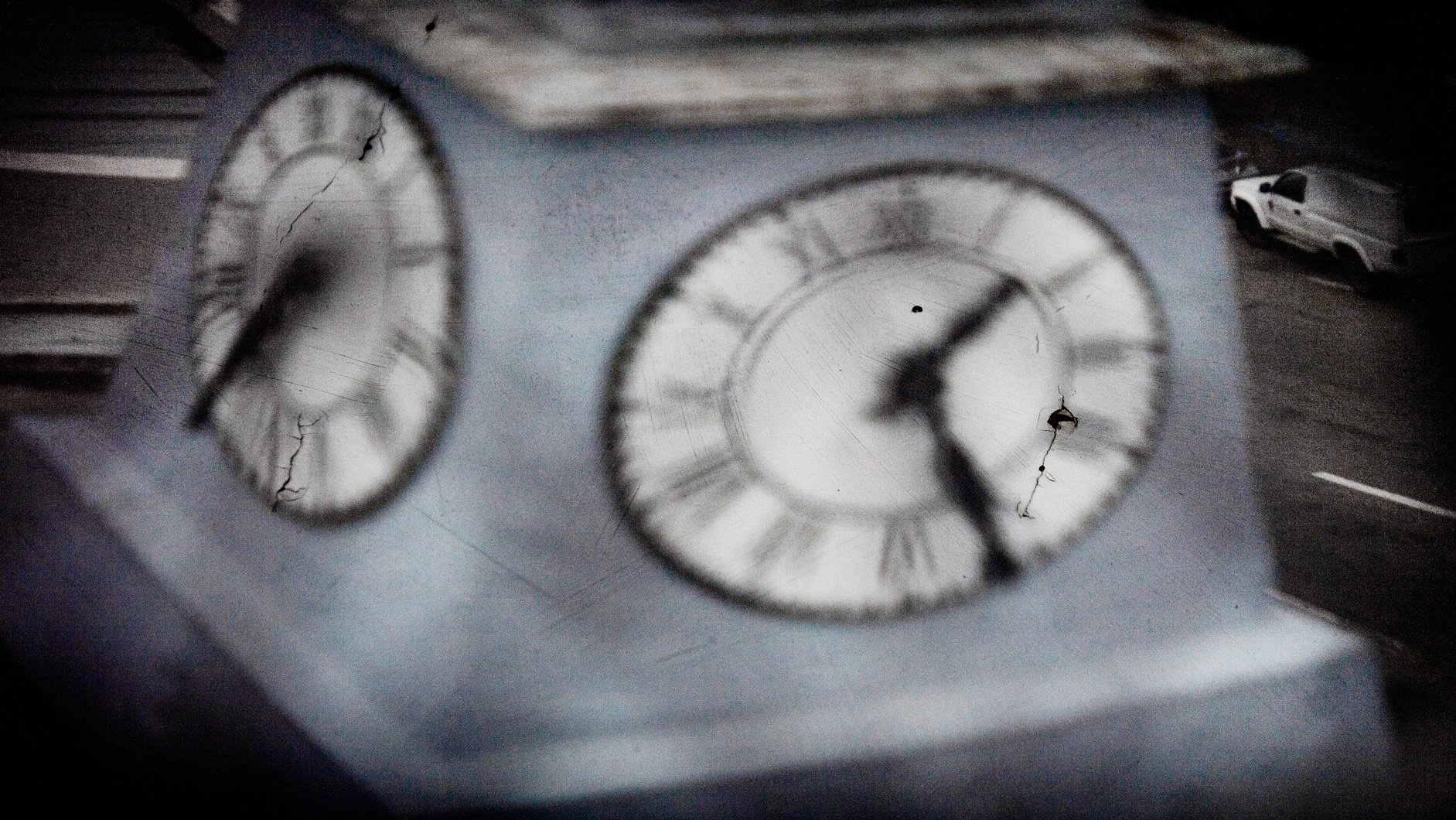

Public monuments instruct us on what to remember, tell us what is worthy of recounting, show us where our collective sympathies lie – if only momentarily. Time moves on, and quickly. Plot points change; themes pivot. A new parliament takes its seats.

The flaws of past ambitions become apparent. The commissioning of new monuments demands a disregard for these shifting sentiments. We are destined to live in towns and cities cluttered with outdated idealism. And perhaps that is the monument’s singular lesson.

Of those smaller monuments, those incidents of a life lived, a single request: remember them, though you may not have known them. Hold off forgetting for a short while.