Part I: The prison and the fort

A cross-section of the first colonial structures in Hong Kong and Cape Town: Vabre Chau and Davids take these two cities as nodes of postcolonial tension which forms the basis of the cultural research coordinates to map their inquiry. Ranging from playful similarities to complex historical connections that inform larger political structures, they explore the depth of their intertwined realities and notice how seemingly disparate elements can influence cultural landscape.

L.D. Amandine and I met in London, where we were both fellows of New Curators (a hands-on training programme for aspiring curators from lower socio-economic backgrounds). After the program, I returned to Cape Town and Amandine to Hong Kong. We called each other to catch up semi-regularly and we began to notice some intersections. With both Cape Town and Hong Kong positioned as postcolonial port cities, our initial interest revolved around comparing their historical and urban makeup to think about the contemporary moment we live in.

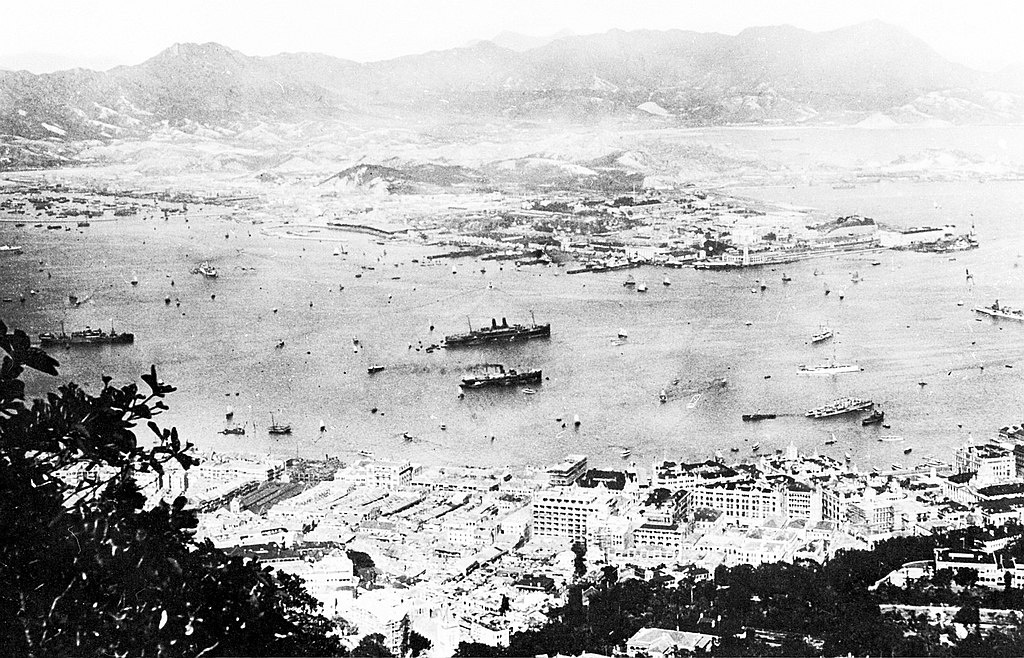

A.V.C. The way a city is planned greatly reflects its intended use and power structures. Hong Kong’s urban development started by the Victoria harbour front, chosen as a good location for the British to monitor the Qing1 government activities, while the Mid-Levels area in Central (halfway up the hill as the name indicates) was quickly developed into Government Hill. All primary government institutions were built around the governor’s residence, showing the desire to establish a centralised power house. The Chinese were slowly pushed out of the area, both directly and indirectly, as Central became the commercial district for Europeans.2

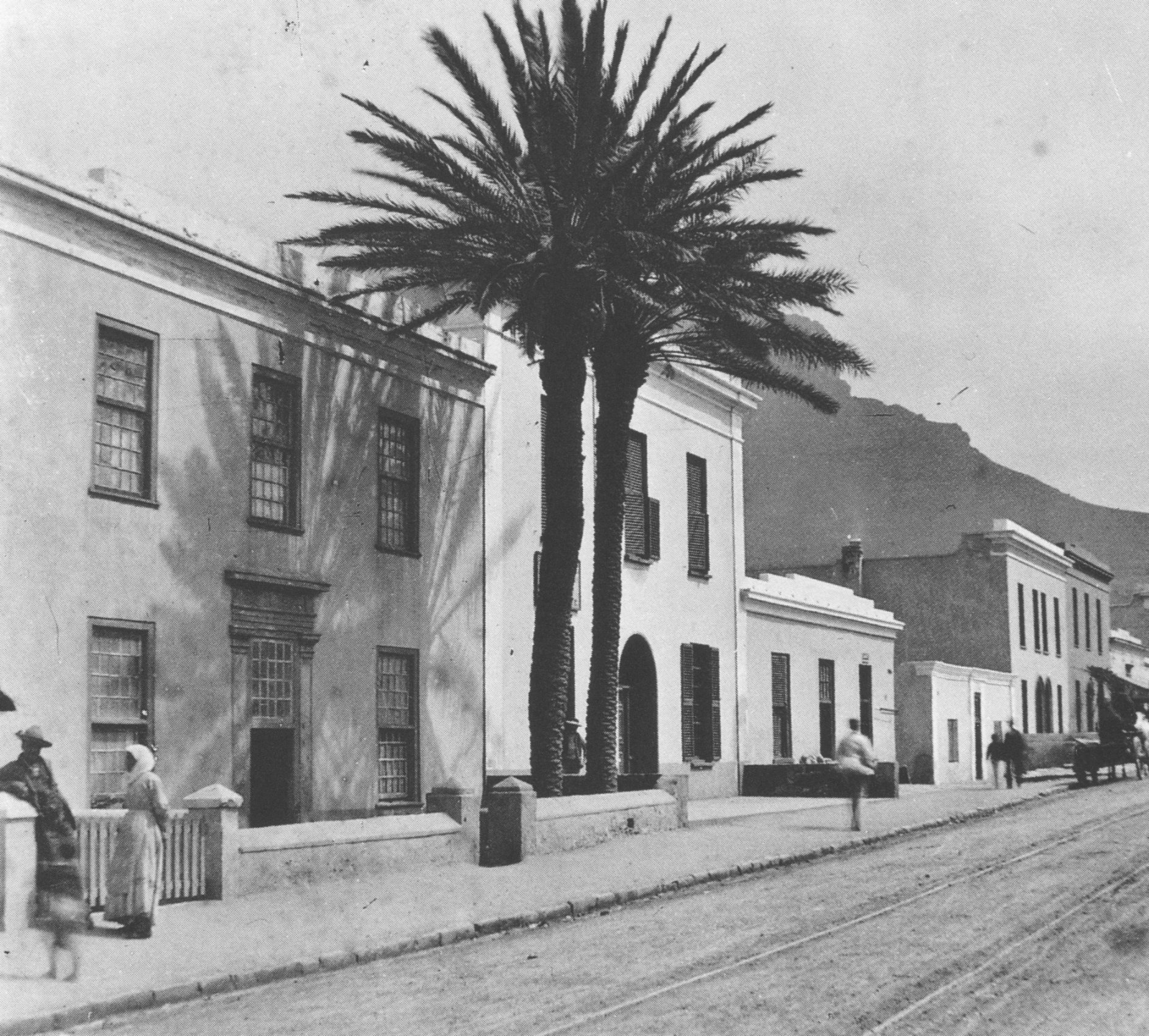

L.D. Cape Town’s urban form reflects its colonial roots, grown outward from the Dutch-built Castle of Good Hope. European settlers established themselves in fertile, sheltered areas near Table Mountain (and its surrounding peaks), close to the city’s economic and political centre. In the mid-20th century, black and coloured communities were forcibly removed out of the central city bowl to the then-barren Cape Flats, under rigorous apartheid urban strategy. These policies cemented spatial inequality into the city’s fabric in enduring ways.

A.V.C. One of the first permanent structures that the British built in Hong Kong was the Central Police Station Compound, situated near government hill. It first comprised of a Magistrate’s House and jail blocks, then later included the Victoria prison. It was a microcosm of multiple key elements of its time, namely racial hierarchy: cultural differences were made to justify harsher punishment to Chinese inmates, deemed accustomed to more severe conditions. This included branding, flogging, and public shaming. Prisoners were also segregated based on ethnicity. Interestingly, inmates were used in afforestation and road construction efforts, showing how forced labour contributed to the landscape that we know today.

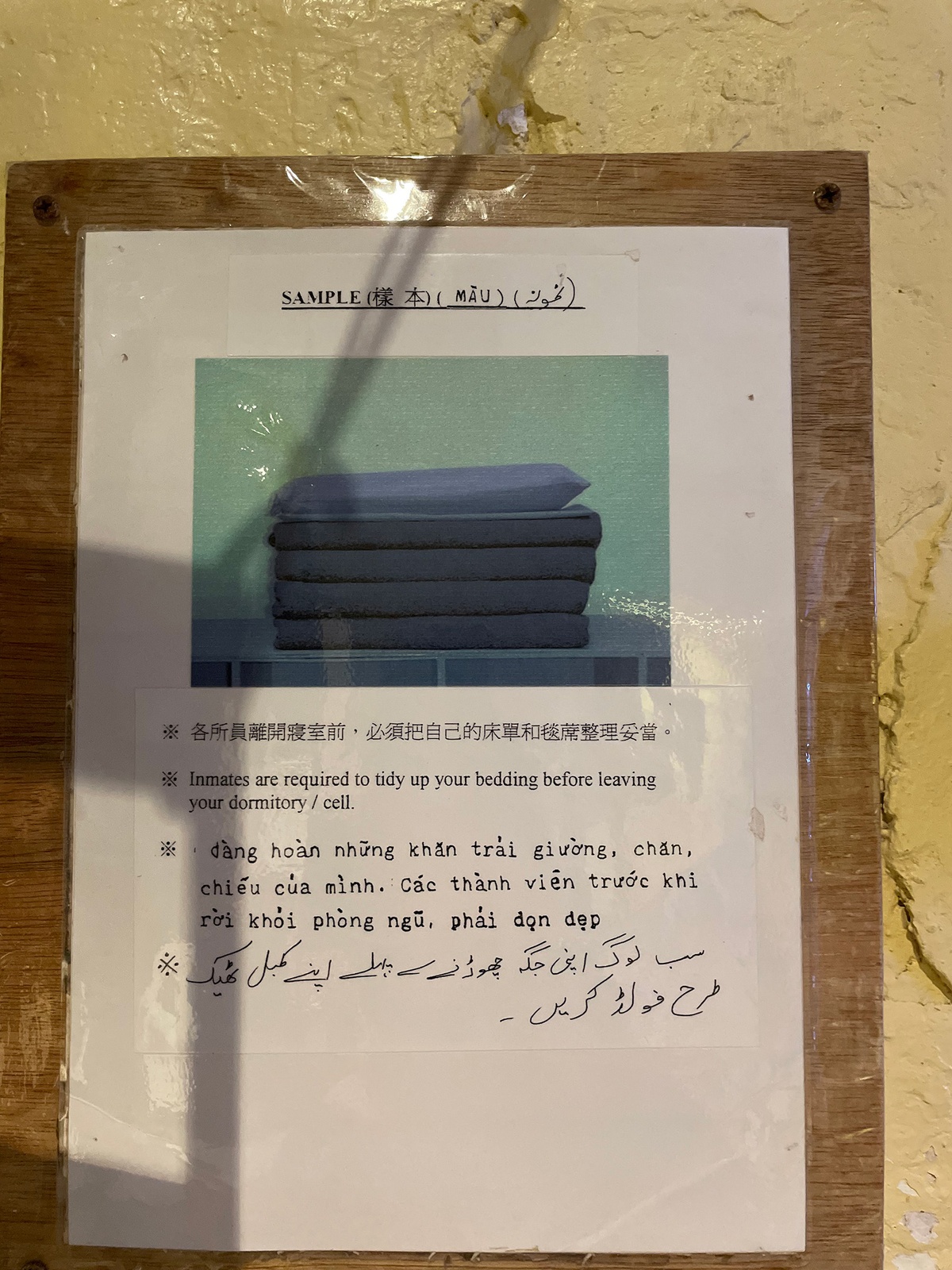

If you find yourself on the compound you’ll notice multiple languages are featured: English, Chinese, Urdu and Vietnamese. The site was a strong multicultural nexus with our first police force including British and South Asian soldiers, foreign sailors, and local Chinese. Upon completion of the Police Headquarters Block in 1919, you could even find a Sikh temple and a mosque.

Later in the 70s, part of the Victoria Prison became an Immigration Department’s liaison office, dealing with the influx of Vietnamese and Mainland Chinese migration. An important moment in Hong Kong history was the refugee crisis of the 70s-80s which was marked by the Huey Fong cargo ship marooned in the harbour, carrying more than 3000 Vietnamese refugees. During this period, the Victoria Prison held those destined for repatriation to Vietnam3. This shows how the complex was a prominent marker of global shifts.

The whole lot was revitalised into a heritage and contemporary art museum named Tai Kwun, its local name. The Bauhinia House, built in the 1850s, is now the oldest remaining structure on the compound.

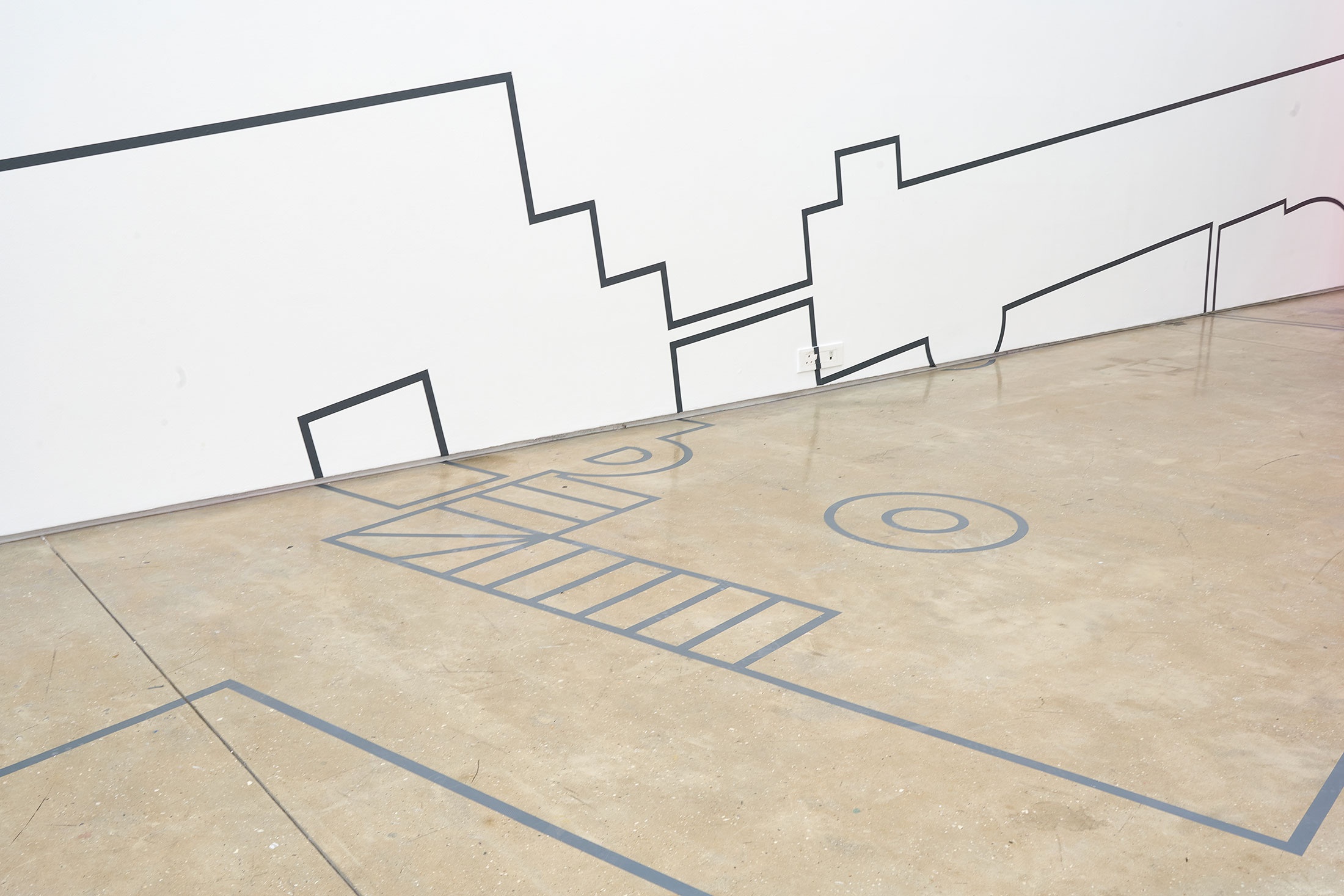

L.D. Alicja Kwade’s exhibition, Pretopia, was on display at Tai Kwun at the time of Amandine’s visit in May 2025. There’s so much haunted history in buildings like these that it becomes difficult to ignore the layers of context when engaging with the site as an exhibition venue. Kwade used the preserved construction materials from the old Victoria Prison site – red bricks historically inscribed with the word ‘UTOPIA’. It’s a paradox in the context of building a prison: “an ideal state that seems on the verge of collapse”4. For me, Kwade’s work brings the suspension of time, weight and space into our conversation around urban material.

A.V.C. I remember standing by the moving sculptures, amazed at how they seemed to float with such ease and difficulty at the same time – like a giant moving in slow motion, heavy and sluggish. They turned on themselves – mobile, but essentially going nowhere, the illusion of change stuck in a loop.

L.D. The oldest existing colonial building in Cape Town is a bastion fort built by the Dutch called the Castle of Good Hope. The first stone was laid in 1666. It marks the old coastline of Cape Town, but now sits on the edge of the District Six area and the city centre, following land reclamation (manual creation of a new shoreline) from Table Bay in the 1930s/40s. When I visited the Castle, I noticed that it’s guarded by two terracotta lions, which the museum claims is in a style suggestive of South East Asian origin.

In a way, I see them as the two stone lions at the gates of this inquiry, especially as Amandine and I have stumbled upon generous lion symbolism throughout our research.

Lion’s Head and 獅子山 (Lion Rock) are two iconic mountain peaks in each city, one of the first physical commonalities we noticed. Both were named after their shape: a lion resting in a Sphinx pose. Hong Kong’s lion-form is far more noticeable than Cape Town, wherein you might need to have a higher capacity for imagination to see the lion.

A.V.C. They’re also popular hiking trails. Lion Rock is a cultural symbol that we all grow up with, even as diaspora. It became notorious due to the TV series Below the Lion Rock, depicting the everyday struggles of Hong Kong people. The mountain is often mentioned to create a sense of unity, and is frequently featured as backdrop during major social upheaval, with people climbing it or unfurling banners from its peak.

L.D. To return to the castle and prison, the Good Hope fort was also used as a detention centre during the Anglo-Boer War (a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics at the turn of the 20th century). Similar to the trajectory of Victoria Prison turning into Tai Kwun, it was later declared a heritage site 30 years on, and transformed into a complex of historical museums which still exists as today.

A.V.C. It’s interesting that you mention the Anglo-Boer war. After their victory, the British needed labour for the mines in Johannesburg, and recruited (or trafficked) many Chinese contract labourers. The Chinese workers’ settlement was situated on the present-day Jao tsung-I Academy, now a historic building complex in Lai Chi Kok, Hong Kong. These workers were derogatorily referred to as ‘coolies’ by the authorities and locally as ‘piggies’, while their quarters were called ‘pigpens’. It came from the idea of these people being tricked and sent away like livestock. Between 1904–1906, South African mines recruited more than 60,000 Chinese labourers, 1,741 of whom stayed at that compound.

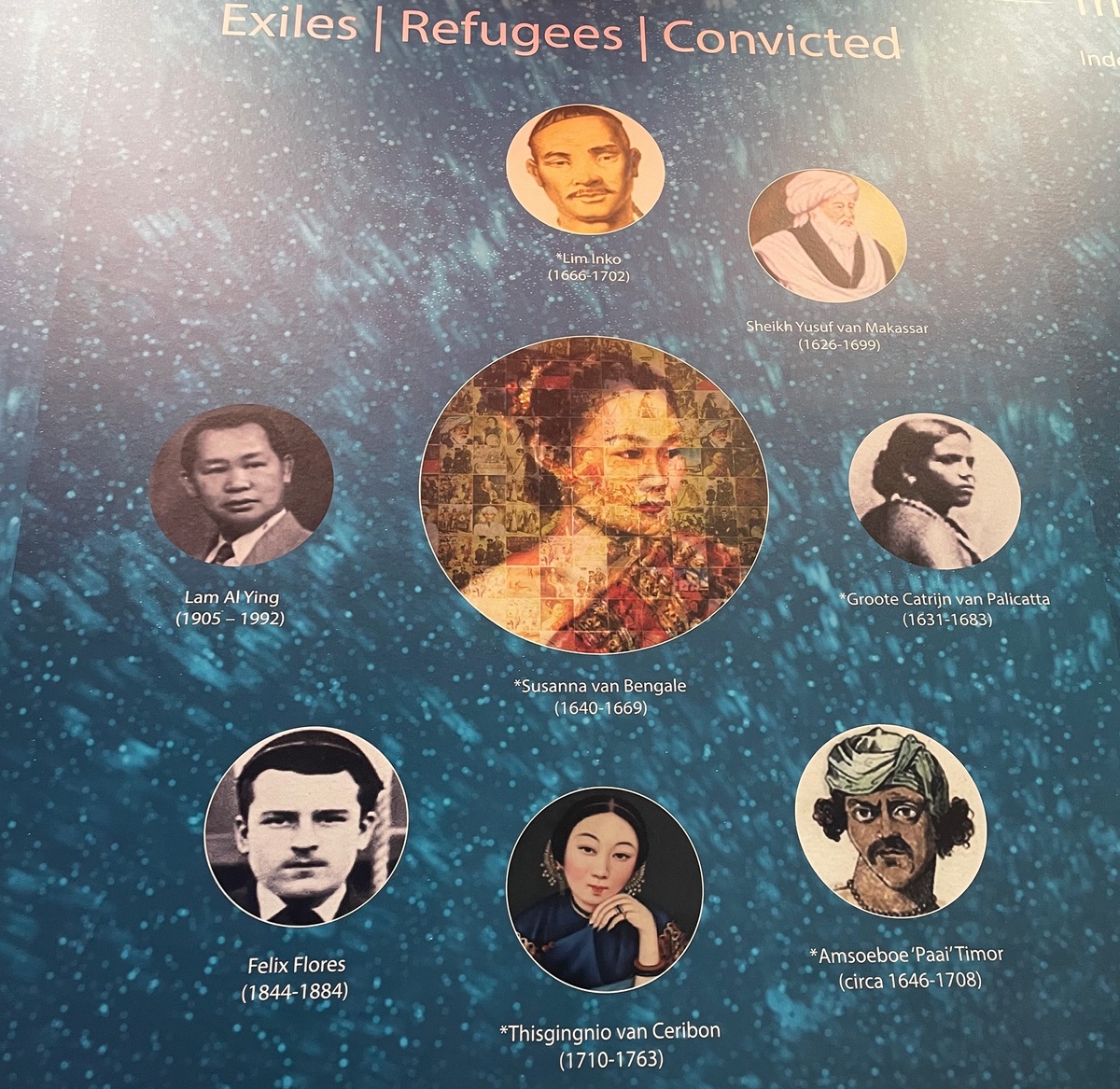

L.D. Chinese immigration to South Africa happened in a variety of ways. In the Castle, I came across an exhibition in a room called the Camissa Museum. It focused on Cape Indigenous African identity and explained the various ancestral ‘tributaries’ that contributed to the larger ‘river’ of hybrid identity. One of the tributaries marked ‘Exiles | Refugees | Convicted’ included many East and South Asian political figures, who had been banished to the Cape for challenging Dutch imperialism in South Asia.

A.V.C. Both buildings we mention are of an enforcing and policing nature, which is important to think about. They are also built in quite telling places: up a hill or by the coastline, two sites where surveillance can be easily carried out. They function as anchors both in governmental organising and the wider urban landscape, showing how vital urban development is in understanding a city’s fabric.

Part II: Shaping the land

An exploration of botanical importation and landscape architecture as structural tools in Hong Kong and Cape Town.

A.V.C. Landscape architecture is an integral part of government policies and closely connected to urban planning. The manner in which an administration engages with nature is revelatory in the sense of it often echoing its relationship with its inhabitants.

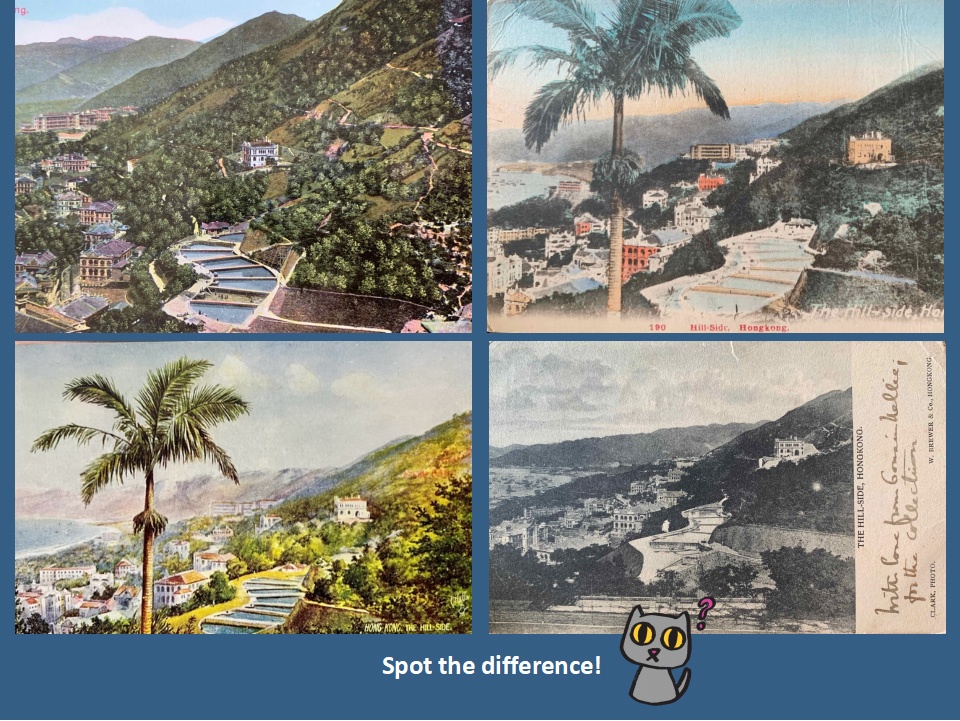

I first became curious about palm trees after attending a talk at Asia Art Archive. Vivian Ting, a researcher and curator in Hong Kong, was one of the speakers. She explained that palm trees were largely introduced to Hong Kong and Indonesia during British colonisation. They realised the rubber industry was in decline, and, predicting palm oil to be a major product in the 20th century, decided to import and plant them throughout the territory.

It is worth noting their prominent presence in inhabited areas, rendering them important markers of our visual geography. Palms have been easily associated with a tropical fantasy, their visibility prompting us to question how they can shape both our physical surroundings and internal imagination.

L.D. In the Cape Colony, the Dutch brought over Muslim indentured workers and slaves from South Asia. To practice their faith, they required a place of worship, leading to the construction of the Palm Tree Mosque around 1780. The mosque is credited as being one of the oldest unaltered buildings in Cape Town and has a wild date palm (Phoenix reclinata) outside of it, likely brought in from the Arabian Peninsula or other parts of Africa. It's unlikely the original tree because palms usually live for 100 years.

Amandine and I spoke with Dor Guez who shared an alternative point of view in the context of his Palestinian hometown, Lydda. Instead of palm trees (which are native to the Arabian peninsula), it was the alien pine tree – seeds from South Africa, planted on top of village ruins – that was a marker of this ‘intentioned’ landscaping, making the environment appear more European. The alien trees began to fall over, drawing more attention to the very destruction they were trying to hide. In our conversation with Dor, Amandine described the history of tree planting in Hong Kong, and he echoed the similarities with occupied Lydda as a key connection city, in-land from the port of Jaffa.

A.V.C. It was interesting to hear the similarities, it often feels like we’re studying isolated cases until we connect the dots. There were large afforestation efforts in the 1870s here. It started from planting trees along main streets for shade and aesthetic purposes, which mainly happened around European areas5, then private gardens inspired by British ones. It finally expanded to the rest of the territory as the administration thought to ‘dress’ up the ‘barren’ landscape. As mentioned in the previous section (The prison and the fort), prison labour was significant in this effort, along with local Chinese labour.

L.D. The palm tree element reminded me of Pear_ed (a collaborative research project on botany and art, comprising Cynthia Fan and Hayden Malan). Their Hypothesis 1, staged at A4 in 2023, featured woven palm fronds and dates that created shadows mimicking barbed wire. I spoke to Pear_ed about our Hong Kong/Cape Town curiosities and they mentioned that palm trees are great candidates for ‘decorating’ a city because they have shallow roots and shed leaves in a controlled way. There was also a possible ideological thinking behind it, with the palm being a somewhat strong architectural form. It ties into ideas of ‘taming’ the land.

Jan van Riebeeck’s Hedge in Kirstenbosch Gardens comes to mind; sprawling almond trees that were planted in 1660. They demarcate the settlement boundary of the first Cape colony, as the South African National Biodiversity Institute states: “For many, this hedge marks the first step on the road to apartheid and symbolises how white South Africa cut itself off from the rest of Africa, dispossessed the indigenous people and kept the best of the resources for itself.”6

A.V.C. That’s why I think researching landscape is fascinating, we delve into the way natural environments get co-opted. The desire to embellish Hong Kong’s terrain was linked to ideas of purity – of a nakedness to cover – and of ‘hygienising’ the city. This, along with a discourse on locals destroying their own environment, led to a saviourist narrative of the British ‘restoring’ it to its glory. It was quite symbolic of their civilising mission: acclimatising and regulating the land, shaping it to their image, and visually asserting authorship and ownership. Altogether, it culminated in the establishing of the Hong Kong Botanical Gardens, closely linked to the imperial network of Kew Gardens in the UK7.

L.D. Earlier in the conception of 6414.36 nautical miles, we were talking about a series of books that Kew Gardens published in the 1800s on the British territories at the time. The floral surveys included the Cape and Hong Kong, amongst the West Indies and British India. Herbariums and gardens have often come up in our discussions about this project. I think there’s something so obviously political about them, even if they are largely beautiful public open spaces associated with alleged scientific objectivity.

Part III: Perlemoen / 鮑魚

Abalone as a cross-cultural symbol of trade, cuisine, and ecology, through the lens of artistic engagement.

L.D. Haliotis midae – 鮑魚 (abalone) or perlemoen – is a protected sea snail species found on South Africa’s coastline. They are known for their recognisably iridescent ear-like shells with respiratory pores, clawed pearls, and in some parts of the world, as a luxury food item. Abalone takes up to ten years to reach maturity, so although it can be defined as a replenishable resource, the demand outweighs the supply. A 2018 report by TRAFFIC, a wildlife trade monitoring network, noted that historically about 90% of African abalone is exported to Hong Kong, with 65% of these exports being illegal.

A.V.C. To say that I am shocked would be an understatement. This isn’t widely known in Hong Kong. Most have heard of South African abalone without truly noticing it, similar to something existing in the background that only comes to light when you point it out.

Import sources also include Japan and Australia, and it’s usually eaten for special occasions. Nowadays it’s widely available and relatively cheap, despite still being considered a delicacy. I don’t think I would’ve noticed this menu before our discussion, and certainly not its implications.

L.D. To retrieve the abalone, the divers brave riptides in the darkness (as using lights would increase detection), then run their catch across open velds, and resort to illicit connections who are familiar with smuggling to facilitate trade. These syndicates often, historically and currently, introduce narcotics into South African fishing communities as payment for the abalone.

The snails’ striking iridescent shells are discarded as soon as they’re shucked. Jody Brand, who lives and works in Kleinmond (an abalone poaching hotspot), pointed out some remnants on a river bank during a studio visit. She repurposed these shells to create a rosary-like work in remembrance of her late grandmother and as a meditation through a turbulent time in her family.

I’m interested in the idea that abalone is normalised in Hong Kong because I found a company that sells abalone in South Africa, and their FAQ page contains questions like: “Is eating abalone ethical/legal?” This unsuspecting snail connects contemporary ecological issues like overfishing, economic terms of trade, and indigenous knowledge preservation. Historically, the sea snail was harvested by the strandlopers, coastal foraging communities connected to KhoeKhoe ancestry. A lot of this knowledge of abalone becomes lost – how it tastes, how to eat it, where to find it – and obscured through poaching.

A.V.C. The way each place engages with their resources is very telling of both local and global dynamics. Abalone shells are also used by Hong Kong artist Wing Po So. She comes from a family of Chinese medicine doctors and often uses medicinal ingredients, including abalone, that she reappropriates and transforms into large-scale installations or sculptures.

She uses built-in motors to make them move slowly, as if breathing, and places them inside salvaged medical cabinets from traditional pharmacies. Her work has a very sensorial quality to it, with materials often coming to life in various ways, showing the interconnectedness of organisms.

Hong Kong has a long-standing relationship with marine life: abalones are part of our cuisine but oysters are more commonly featured as having played a major role in our cultural history. Oyster reefs were extremely prominent in this area but most are gone nowadays. That explains why artists are inclined to use this mollusc as a potent symbol for Hong Kong history and culture.

In Palimpsest, Jes Fan documents the meticulous work of implanting living oyster shells with the individual characters, 東, 方, 之 and 珠 which reads ‘Pearl of the orient’, a title that has been attributed to Hong Kong. The characters are placed flush to the interior surfaces of the mollusc, which begins to respond and contend with the intrusion in order to survive.

L.D. The significance of this discrete animal, perlemoen or 鮑魚, is that it represents a cultural intersection between Hong Kong and Cape Town. The link is forged by an AfroAsian trade route – a connection between Cantonese cuisine and the strandlopers of the Cape.